Montevideo, Santiago de Chile and points in Argentina

16 September - 6 October 2019

16 September - 6 October 2019

photos by G.P. Jones using Nikon D3400 digital camera,

except where noted

[A brief advice about copyrights: I respect intellectual property, and I expect others to respect mine. My photographs are copyrighted. They may be used freely, including reposting on the Internet, on the condition that credit is given to me as their creator, and on the further condition that they never be used by anyone for commercial purposes or financial gain. As for the content of any photographs on this page, if the copyright or intellectual property of any other person or institution is compromised, I will remove the image from the page upon request.]

Itinerary

The central purpose of this trip was to further my knowledge and

collect more original photographs of angel sculptures and other

works by Italian artists working (or delivering their work) in

South America.

Success in these pursuits was easy, as many Argentine, Chilean and

Uruguayan people are of Italian descent - as many as 50% of the

population of Argentina, I was surprised to learn - and in the late

XIXth century, when Italian immigration was relatively 'new', it

must have seemed logical to them, when planning for their grave

monuments or civic statuary, either to bring Italian artists to

them, or to have such artists send their work by ship.

A few artists jumped out at me (so to speak) as being particularly popular, and I will feature them throughout this travelblog [sic]. They are (in alphabetical order), Alessandro Biggi (1848-1926) [sometimes known here as Alejandro Biggi], Leonardo Bistolfi (1859-1933), Achille Canessa (1856-1905), Giovanni [Juan] Azzarini (1853-1924), Émile Edmond Peynot (1850-1932).

Of course, local artists also are represented, and even some from France (Peynot, for example, just listed above). Other themes will include the usual Thanatos Angels (the angels who attend to, and mourn, the deceased), Guiding Angels, public sculpture and bizarre encounters (including civic graffiti). (See other travelblogs on this Web page for more examples of these.)

Montevideo, 17-18 September 2019

Leonardo Bistolfi (1859-1933) was well-represented on this trip, in

cemeteries as well as museums.

The theme of this detailed work (1913) in the Cementerio del Buceo in

Montevideo is similar to others I've seen in Torino, Budapest

and elsewhere: mourners carrying the deceased in a coffin or on a bier to

her or his burial.

These aren't just pallbearers - everyone in the community shares in the

honour of bearing the dead to a final rest.

There's another example below (i.e., later in my trip) in Rosario.

This is Bistolfi's signature on the right-hand side of the base,

near the front.

Juan [aka Giovanni] Azzarini (1853-1924) gave several sculptures to

Buceo, including these two angels - on two different graves - who not only

could be brothers, but tend to pose in the same position (!), except that

one appears to be left-handed, the other right-handed.

I am quite sure the ropes around this statue's neck are to stabilise

the bust on the pedestal, and are not part of the original artwork.

This touching monument (1901) commemorates the work of a Montevideo

"medico filantropo", who apparently concentrated his efforts

on the poor, indigent and disadvantaged of his community.

The inscription notes that the memorial is from "sus amigos"

(his friends).

Sometimes a cemetery sculpture or inscription can only be described

as 'heartbreaking'.

The Cementerio del Buceo is a peaceful, bucolic place.

It is open to the public, though visitors who want to take

photographs need to register in the main office and get

official permission, which includes an ID tag that must be worn

as a necklace throughout the visit.

(This is the only cemetery I've seen yet where this kind of

permission is necessary.)

When they grant permission, they ask you to try to avoid photographing

the names of deceased individuals or families, out of respect.

They remind you that Buceo is a private, not a public, cemetery.

Santiago de Chile, 19-21 September 2019

A niche in the Cementerio General of Santiago de Chile.

I imagine this awning is there for a reason, which totally escapes me.

Imagine the chutzpah of a builder putting his telephone number on

a tomb that (obviously) will outlive him and his business.

Marketing knows neither boundaries nor ethics.

Pabellón is a form of the word "pavillion".

Many cemeteries have a Remembrance Wall such as this, commemorating

individuals in small tiles or inscriptions.

This type of memorial is common throughout the world, from the

Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington D.C. to the informal

graffiti and pictures on the "Tortilla Wall" on the

U.S.-Mexican border in Southern California memorialising migrants

who died trying to enter the United States.

A reminder that Spring begins to spring in September in this part of the

world.

The Patio Historico is the oldest part of this cemetery, though the

age of this particular citrus tree is unknown (to me).

The Cerro San Cristóbal, the second highest point in

Santiago de Chile, looms over this Cemetery.

The tiny white figure at the top is the 22-metre statue (including

the pedestal) of the Blessed Virgin Mary which commemorates

Pope Pius IX's declaration (1854) that the Immaculate Conception of Mary

was official church doctrine, not just common belief as it had been since

late antiquity.

A street leading up to the Cerro San Cristóbal is named Pio Nono

after Pius IX.

More on this below.

Some cemetery mausolea are enclosed, such as the Capilla Verde seen

below. Some are little more than stacks of boxes

(no disrespect intended). Still others are fine examples of cemetery

architecture, such as these with a Moorish influence.

The Capilla Verde (Green Chapel), built in 1900, which to me looks more

gray than green, is so named because of the green-tinted Ranquén

stone used in its construction. (So says the information plaque in

its forecourt.) It is big and strong with Greco-Roman columns

and many internal hallways and galleries. Persistent local legends

regarding voices inside and mysterious circumstances of some of

those interred are given life in the regular night-time tours

conducted here.

(By the way, night-tours in cemeteries, especially in South America,

have become quite popular in recent years.)

Local institutions and societies sometimes have their own

dedicated Panteones (mausolea).

This one is for the Carabineros (national police) de Chile.

Mausoleum styles include abstract modern (my term, not necessarily

an authentic name for an architectural style).

Other family tombs are built with a mix of styles.

Here Greco-Roman columns mix with a Renaissance-type dome, and Gothic

stained glass. (Again, these are my terms; consult a real art historian

if you want accuracy.)

Claudio Vicuña engaged Italian-born architect

Tebaldo Brugnoli for his family's colonnaded

mausoleum (1896), complete with a staircase and guardian lions.

The Islamic-style dome originally over the palatial interior was

dislodged by the 2010 earthquake in Santiago de Chile, and later removed.

Art Deco Ornate. (I make up architectural terms as I go along!)

Art Deco Understated.

In this mausoleum for the Justiniano family (1927) and bronze

by French sculptor Alphonse-Camille Terroir (1929)

the Deco influence is subtle, and perhaps for this

reason, I found it all the more moving.

(It was not easy to find; it's located in Patio 44, at the East

side of the Cemetery near the intersection of the paths called

Alejandro del Río and Dávila.

A cemetery worker helped me find the monument, after which she gently

reminded me that a propina [tip] might be appropriate.

I agreed, of course.)

A few steps from the Justiniano mausoleum is this tiny sculpture,

no more than a metre wide, at the memorial for General Carlos Prats

González (1915-1974), who was assassinated during one of

Chile's many politically turbulent eras.

There is quite a bit of intrigue in this story, including an American-born

assassin who as of this writing (2019) is still living under a

witness-protection cover, at least according to Wikipedia.

'Nuff said about that.

The sculpture is credited to Mario Covarrubias Irarrzaval (born 1940).

The more I visit cemteries around the world, the more inevitable it is

that there will be a copy (or look-alike) of the

Monteverde Angel

first sculpted for the Oneto tomb (1882) in Staglieno Cemetery in Genova.

As cemetery sculpture moved into the XXth century (so to speak), it was

no longer necessary to shroud erotic images in the form of

topless angels, or

barely-clad dying saints and Saviours. (Hey, I just tell it like it is - or

was.) This sculpture by Antonio Morera (1888-1964) from 1925 is called

El Dolor y La Aspiración (Grief and Aspiration, or

perhaps, Pain and Yearning).

This cemetery (like that of any city anywhere) is full of history,

though most of it is not obvious in the monuments and tombstones themselves.

This is the grave of Julio Covarrubias Freire (1896-1920), who

died in a politically-motivated attack during Chile's presidential election

of 1920.

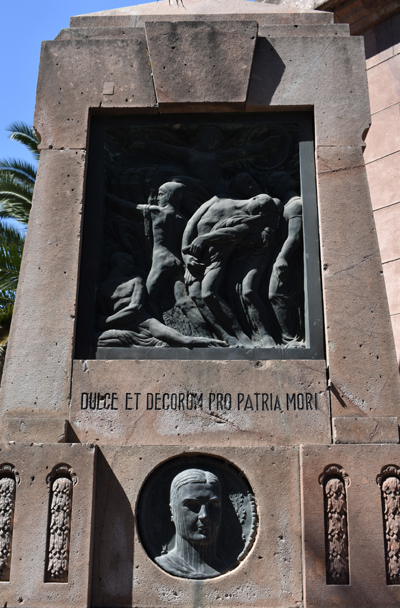

The inscription - DULCE ET DECORUM PRO PATRIA MORI - is a modified

version of a line from Horace (Ode III.2.13). (The original has EST after

DECORUM.) It is usually translated, "It is sweet and proper to die

for one's country."

The phrase virtually disappeared from common literature after World War I

antiwar poet Wilfred Owen used it in the title

for one of his poems, and referred to it as "The old lie".

(Second Lieutenant Owen was killed in action, aged 25, just two years

before this grave was constructed, and some 6,000 miles away in an

unrelated war.)

My travels have brought me in contact with several images like this.

Some I have sought out (like the staute of Joseph Bara in Palaiseau,

France, visited earlier this

year and documented on this Web site in my travelblog for that trip),

and some, like this one, encountered by chance.

Either way, I find fascinating the history or legend

of very young men or boys who go to war - and often,

later, are made heroes primarily because they were so young.

This sculpture in Santiago's Museo de Bellas Artes is by José

Miguel Blanco Gavilán (1839-1897) and is called

El tambor en descanso (literally, The Drum at Rest, 1884)

The Hotel Castillo Rojo in Calle Constitución, a boutique hotel

I highly recommend - my residence in Santiago de Chile.

It is one block away from the hipness of Pio Nono (the street named

after Pope Pius IX, which I referenced above).

Pio Nono (Pope Pius IX, after whom this street was named) never saw

anything like this, I bet.

American hip-hop apparently is quite popular here.

Not really hip-hop, but close: Elsa Lanchester

(The Bride of Frankenstein, 1935) wearing a

sweatshirt for The Lost Boys (1987).

All I can say about this urban art work is that it was not

PhotoShopped. What you see is what I got.

I'm pretty sure this graffito says, "Muerte al Macho" -

"Death to Macho" (or, closer to home, the literal translation,

"Death to the male" - I hope that's not the intention!).

Of course, with the stylised 'C', it could say,

"Muerte al Matho" - but who would wish the demise of Math?

This artwork, the entrance to a (defunct?) pizzeria, is much clearer.

Both the word and the hand sign indicate the classic, Italian

curse of the Evil Eye.

Santiago de Chile may not be that safe of a city (though I never felt

ill at ease or in any danger).

This routine, middle-class house has a rather serious-looking electric

fence (not to mention a spiked, iron rail) around its high wall.

Aside from being politically incorrect (at least by American standards),

this mannequin advertising a printing establishment is oddly placed

relative to the street and the door.

But who am I to judge?

Even decrepit, and possibly long-unused, buildings can be interesting

if painted correctly.

Modern sections of Santiago de Chile can be striking, indeed.

The architecture of this high-rise office building "works"

in my opinion, and is not alone by any means.

The financial district of Santiago sometimes is referred to as

"Sanhattan".

Santiago, like Buenos Aires, seems to enjoy paying homage to other

cultures, particularly European countries from which many Santiagoans

originally came. (I made up the word Santiagoans. I hope nobody minds.)

This civic monument is known as

Fuente Alemana (German Fountain).

It was created in 1912 by Gustavo Eberlein (1847-1926), restored in 1997

and then restored again in 2011.

It's really big.

Across the street from the Fuente Alemana is this whimsical,

Art Deco building complete with gargoyle.

Buenos Aires, 22-24 September and 1-5 October 2019

Santiago Lavarello (died c.1910) created this angel and pediment

depicting the Last Judgment in 1882 for the main entrance to

the Chacarita Cemetery in Buenos Aires.

While the (much) more famous Recoleta Cemetery (see below) came to be

the burial place of the rich, this is generally considered

the "people's cemetery" for the city.

Chacarita Cemetery's centrepiece (perhaps by design, perhaps not)

is this ornate Panteón designed by Alejandro Christophersen in 1896.

A sitting sculpture is so unusual in a spot like this that it is easy

to imagine some kid has climbed up there just for fun - until you notice

the wings.

I will always wonder why the 'vegetation' grows only on this statue's

face, and not over its entire body.

This is genuinely creepy.

This mausoleum is not what you may think (if you don't know Latin).

MEMENTO HOMO = Remember, man. By themselves these words have little meaning,

but Catholics will recognise them as the first words of the Lenten

reminder, MEMENTO HOMO QUIA PULVIS ES ET IN PULVEREM REVERTERIS -

Remember, man, that you are dust, and to dust you will return.

(Yes, I had to look it up.)

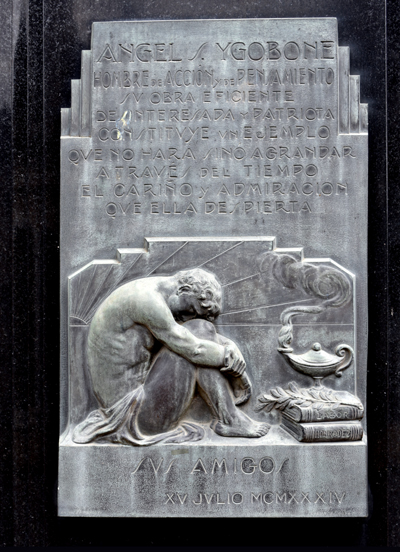

Many tombs and other surfaces have had plaques added which give tribute

to people other than the original deceased.

These are known as homenaje plaques, and often bear a

symbolic or even actual image of a mourner, either angel or human.

This image is borrowed from the famous Jean-Hippolyte Flandrin (1809-1864)

painting [1836] of a man sitting on a rock by the sea,

which hangs in the Louvre.

(I discussed this painting and its many, many variations in a 2014

vacation-pictures page on this Web site.)

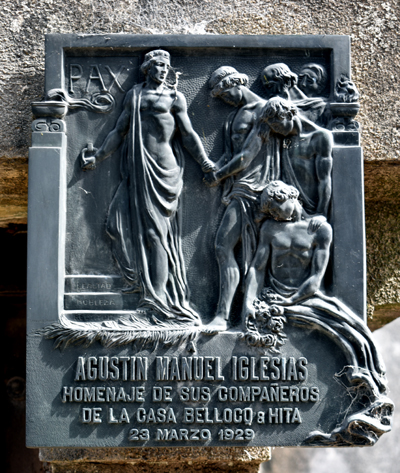

Homenaje plaques often are placed by friends and/or colleagues

of the deceased.

In this one, it seems some very sad compañeros are saying goodbye

to their friend who is about to go through a door marked PAX.

The steps are inscribed with the words, lealtad, nobleza

and rectitud (loyalty, nobility and righteousness).

The word PAX (peace) is found on many tombs in Argentine and Chilean

cemeteries, more, it seems, than in other places I've visited.

It's not clear (to me) whether it refers to the peace of eternal rest,

peace after a world of conflict, or some other meaning.

Modern sculpture really stands out in older cemeteries.

This tomb is 'signed' by the artist (or architect) Carlos de la

Cárcova (1903-1974).

It looks like Art Deco style to me.

Wikimedia Commons

has categories for

Statues of angels pointing up and

Statues of Tuba angels (i.e., Angels holding horns).

This sculpture fits both categories.

Angels pointing up can be regarded as Guiding Angels (the new category of

Angel that I've proposed in recent writings and posts).

The Tuba Angel usually is some version of a Resurrection Angel, whose

task is - or will be - to announce the resurrection of the dead and

the Last Judgment.

(Remember the Last Judgment pediment on the main entrance of this

Cemetery? That angel has a horn. See above.)

The Pellerano Family tomb, near Chacarita's main entrance, is titled

El beso de la muerte (1931, sculptor unknown to me).

That's Death on the right, in the shroud (as usual),

giving the kiss to the deceased to make it official.

Here's another monument steeped in the City's history.

Augusto Vandor was the head of the Metallurgical Worker's Union - note the

abundance of metal surrounding his figure, a fitting tribute like

few others!

Unfortunately, Vandor was assassinated in his union office in 1969.

The sculpture of Vandor and the two side panels are the work of

Pascal Buigues (1897-1980).

I'm calling the Cendon Minellono mausoleum as Art Nouveau.

(The Facebook site

"The World Art Nouveau" agrees with me.)

This mausoleum for the Roverano family is interesting for several

reasons.

First, on it's face, the bas-relief signed by Luigi Trinchero (1862-1944)

is a detailed depiction of the family paying tribute to their late father.

In addition, the shrouded bronze figure, standing in the midst of

(intentional) broken building parts, is signed by the prolific

Leonardo Bistolfi (1859-1933), whose work was seen before on this trip in

Montevideo, and will be seen again later.

As if that all weren't enough, Web sources describe the mysterious

inauguration - and complete sealing - of this tomb (around 1909) with

comparisons of its gold-plated interior to the burial vaults of

Tutankhamun in Egypt, found a decade or so later.

According to very helpful Cemetery staff, the Bistolfi bronze was

added around 1913.

The monument for the J.B. Viglino family has angels from top to bottom.

The one on top, my helpful informant in the Chacarita office tells me,

has several copies elsewhere in the Cemetery, and this one is believed

to be the original.

The date is not known, but is probably sometime around 1899.

Adjoining the Cementerio de la Chacarita - and probably at one time

part of it, as it claims to date from 1820 - is the now-separate

German Cemetery.

The inside of the German Cemetery's main entrance has the inscription,

from John 11:25, which online translations render as, "I am the

resurrection and the life. He who believes in me will live, whether he

dies immediately." (The familiar passage suffers a bit in the

[online] translation.)

Opposite the main entrance gate, the Chapel has another familiar

quotation for those who know Brahms's Ein deutsches Requiem,

or the German version of the Revelation of St John the Divine (14:13):

Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord.

Next to the German Cemetery is the British Cemetery.

They were once one and the same, and were separated,

most interestingly, by a wall sometime in the early XXth century,

ostensibly as a result of the conflicts in Europe during the World Wars.

The British Cemetery has a World War memorial, guarded by this angel.

In front of the angel shown above is this curious headstone, which

commemorates one S[amuel]. Allick, who, it says, is "known

to be buried in this cemetery."

With no disrespect, I will note that the word "Greaser" under

his name gave me a smile.

Surely this was his occupation on the S.S. Empire Might at the time of

his death in 1944.

My first reaction to the word was completely unrelated to Seaman Allick -

to me, growing up, a 'greaser' was a particular type of street kid whose

'look' involved lots of hair cream, giving him a 'greased back' hairdo.

Just one of those cross-cultural jolts that are unavoidable in foreign

cemeteries.

(My apologies, Samuel. RIP.)

With the conflicts in Europe long finished (and the fact that the Germans

apparently were not involved in the Falklands/Malvinas debacle), the

powers-that-be decided in 2018 to

commemorate the centenary of the end of World

War I by opening a gate in the wall between the German and British

Cemeteries, using verbal imagery

that could have been used for the fall of the Berlin wall (a similar

barrier):

derribamos el muro que nos separaba . . . -

We tear down the wall that separated us.

(Note, however, that the gate is locked.

I guess you can never be too careful.)

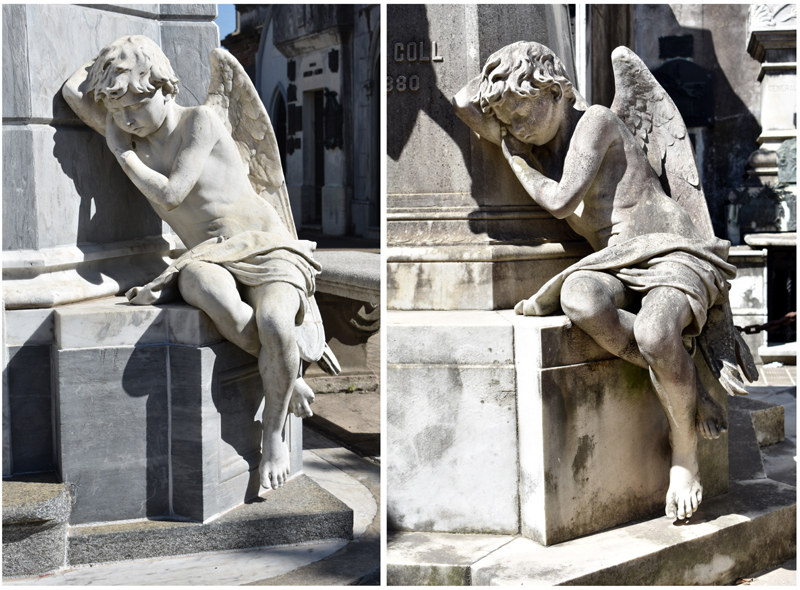

Over in the Recoleta Cemetery, there is a fascinating comparison

available to those willing to search.

The Angelito on the left is well-known - said to be the most photographed

statue in the Cemetery - mourning at the side of the Francisco Gómez

family tomb which was most likely sculpted by Alessandro Biggi (1848-1926),

whose work we will see again when we get to Rosario.

The cherub on the right is much more difficult to find, and once you do,

you may notice it's virtually identical to his twin, though the overall

monuments are different.

The one on the right is on the 1880 tomb of the family of Dr Ventura Coll,

later also used for the family of Ramón Sardá.

This homenaje plaque features a Thanatos angel, which is not

unusual until you notice that it's a female figure, which is quite rare

for this angel image.

Remember Leonardo Bistolfi from Montevideo and Chacarita?

His work again appears here in Recoleta on the Massone mausoleum,

made after Attilio Massone's death in 1920.

Outside of the cemeteries, Buenos Aires has many civic sculptures,

including this fascinating modern work by Eduardo Fernando Catalano

(1917-2010) known as Floralis Genérica (2002).

It actually is mechanical: the 'petals' of the flower close when it

gets dark, and open to the light.

(The skeptic wonders if it will still be working in this way a

hundred years on? We'll be interested to see.)

Buenos Aires's Jardín Botánico has lotsa plants, of course,

and also a nice selection of sculpture.

Saturnalia is a 1909 copy of the 1900 original by

Ernesto Biondi (1855-1917).

Rosedal is another park, just North of the Jardín Botánico,

where one of the city's

several memorials to Domingo Faustino Sarmiento is found.

This marble sculpture, called Ofrenda floral a Sarmiento

[Offering Flowers to Sarmiento, 1915] is one of three works by

French sculptor Émile Edmond Peynot (1850-1932) that I saw in a

single afternoon, walking from the Recoleta to the

Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes.

Peynot obviously was popular in BsAs.

Another Peynot sculpture turned up in a green space to the SouthEast

of Rosedal, this one a memorial to Aristobulo del Valle (1846-1896)

which Peynot was commissioned to make in 1923.

The group is unusual in that it has several figures facing 'front'

(seen here), and another figure on the back, next to a large shield

with an inscription.

Peynot's 'signature', on the base of the sculpture, has his name followed

by 'Paris', which seems to indicate that the work was made in France

then shipped to Argentina.

Just a calculated guess, I admit.

A little farther SouthEast brought me to the Plaza Francia, where

another Peynot sculpture (1910) commemorates the centennial

of the Revolución de Mayo, and was a gift from France to Argentina.

As such, it is doubly interesting, as the figure with the torch with

young people following seems to echo the famous French Revolution image

in Eugène Delacroix's

La

Liberté guidant le peuple

[Liberty Leading the People, 1830] in which Liberty carries a

flag, accompanied by a pistol-waving boy, an iconic symbol of that

Revolution and another example of boys involved in war.

The interesting difference here is that the genders are reversed -

Liberty (female) becomes a Guiding (male) Angel leading the way,

accompanied now by young women (without guns).

Where the earlier (Delacroix) image was bursting out of oppression,

this later one (Peynot) probably represents progress into the modern age.

Across town from the Peynots, in a very different area of the City

called Plazoleta Olazabal, is a sculpture with a more direct, more

realistic 'message' - Canto al trabajo (1922) by Rogelio

Yrurtia (1879-1950).

This is powerful artwork.

One of my goals on this trip was to re-photograph the impressive Columbus

Monument (1921) by Arnaldo Zocchi (1862-1940),

adjacent to the Casa Rosada (presidential palace).

Last time I tried (years ago), it was surrounded by construction fencing, and

I couldn't get close enough.

Imagine my surprise when the bus passed the spot, and the monument

was . . . missing! In its place was a helicopter landing pad.

I asked the bus driver 'what gives' (or words to that effect), and

he said simply that the monument had been removed.

That seemed pretty unusual, though apparently it's done with some

frequency in BsAs. (For example, the Yrurtia sculpture shown above

originally was somewhere else.)

After asking around, I found out the Columbus Monument had been moved

to a location just North of the Aeroparque Jorge Newbery, Buenos

Aires's domestic airport.

So I went there. Again, there was construction that seemed to block

access, so I went up in the parking structure to get a simulated

aerial view.

There, I saw this striking vegetation wall, similar to the one I

saw earlier this year in the Quai Branli, Rive Gauche, Paris.

Wonders never cease here - the inside wall also is covered with plants.

It turns out that, while there was road construction in between the

Aeroparque and the new site for the Columbus Monument, the workers were

letting people through to see the sculpture.

This view shows the impressive monument, with the City in the background.

Then a revelation. I had seen and photographed the sculptures at the base

on a previous visit, but had not noticed that the allegorical figure of

the woman with the torch (of life, no doubt) at the front is accompanied

by a young angel pointing the way to the New World - a Guiding Angel.

I felt like my 'collection' of this variety of Angel was

reaching critical mass, and now I guess I've got to write the book about it.

In the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, I got a pleasant surprise - a

painting of one of my favourite previous trips, the one in 2011 to

Iguazú Falls.

This 1892 painting is by Augusto Ballerini (1857-1902).

The falls look pretty much the same these days.

Also in the same Museo, we see yet another work by Leonardo Bistolfi,

this time a plaster model for the Federico Rosazza Monument (1909) in

Valle Cervo, Biella, Piemonte, Italy.

This model, like the original in Italy, is quite large. The figures in

the bas-relief are pretty much life-size.

Before leaving Buenos Aires, I asked the desk clerk at my hotel where

I could get a good steak.

He recommended La Estancia (a few blocks from the hotel).

Boy was he right. I went back the next day for a goodbye lunch.

Rosario, 25-27 September 2019

Until now on this trip, I had been only in major cities, the

capitals, in fact, of the three countries I visited.

Now, I venture out into the wilderness, first to Rosario.

Don't get me wrong, Rosario is a decent-sized city, once the

second largest in Argentina - but it's out on its own with not

much around it but some farms and lotsa open space.

This building, originally called the Casa de Espana (as you can see

under the lions on the façade), presented some pretty quirky,

interesting architectural features.

Not far away, the Cultural de Abajo building also had some

detailed work around the top.

While walking toward the river one day, I came across this graffito.

I don't know what it might mean, but it seems vaguely rude.

Kind of 'neither one thing nor the other'.

Moving on.

This graffiti set is explicitly rude, and I apologise in advance to

anyone offended. But it's worth the trip. Stay with me:

the picture on the left is a Google Street™ view from

late 2018, showing only the rude bit.

The picture on the right is how I found it on my walkies.

The crying girl was added, along with the text, "Nani?",

which was meaningless to me, until I got home and Web-searched the

term.

Apparently it's Japanese for "What?",

commonly used in anime and manga to respond to something

"confusing, offensive or mysterious"

(source: Urban Dictionary).

Put all this together, and it's pretty dang funny.

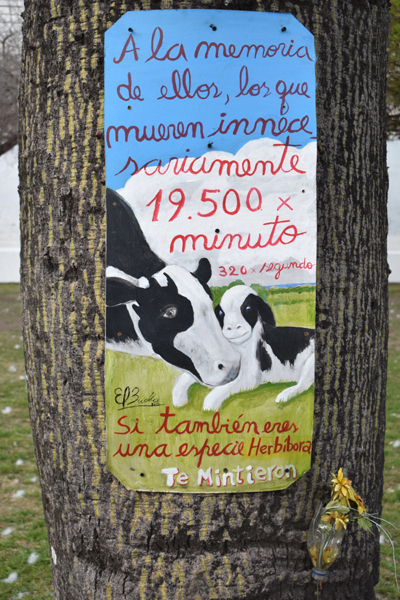

Returning now to somewhat more routine street art, here's an

apparently anti-meat

(pro-vegetarian) poster that seems to bemoan the fact that animals

like these die at the rate of 19,500 per minute (320 per second)[their

math is questionable]. I think the Spanish here might be colloquial

(or even regional), because my online translator renders the text at

the bottom as, "If you are also a herbivore spice, they lied to

you."

A red-haired saxophonist in a Santa suit? Thank God it's only a

mannequin.

(Rosario is a slightly off-kilter place, with all due respect.)

The South bank of the Paraná river is an easy walk from the

center city.

Here, in the pleasant Parque de España,

complete with joggers and a few indigents,

we have . . . a bust of Maimonides (1138-1204) for no apparent reason,

except, perhaps, that he was born in Spain.

This street art, signed along the left by its many artisans, is

unusual and quite beautiful, not to mention in pretty good condition.

Of course, there are mosaics in many cities, but they're usually

'intentional', not found in the form of impromptu street art.

I suppose any street art that requires a ladder must be categorised

as 'monumental'.

This gato (note the tag above the head) is certainly

startling to the average walking tourist (me).

Anyone who says 'street art' isn't art, take another look.

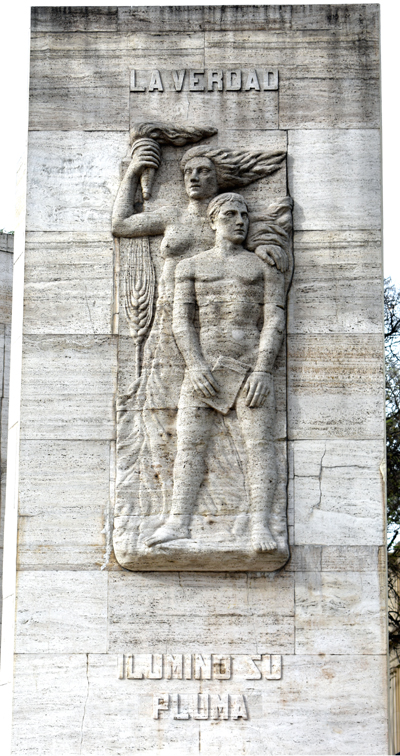

This monument to local historical figure Ovidio Lagos is located,

conveniently enough, on Av. Ovidio Lagos.

Among other things, Ovidio Lagos was a journalist, hence the legend,

"La Verdad illuminó su pluma" - "The Truth

illuminated his pen."

Here we have an allegory (apparently) for Truth - holding the torch -

and perhaps a representation of the journalist himself, who seems to

have suddenly realised that he's not wearing any pantalones.

The Cementerio El Salvador is located across the street from the

Plaza Lealtad, which features a lookalike of Rio de Janeiro's great

Cristo Redentor.

Just inside the Cemetery main gate is this memorial to

Nicanor Frutos, an 'heroic warrior' of the 1866 Batalla de Curupaytí,

sculpted long after Frutos's death, by Guillermo Gianninazzi (c.1880-1948).

As promised long ago (when we were visiting the Bistolfi sculpture in

Montevideo at the beginning of this journey), this is another image

based on the custom of the community carrying the dead to burial.

To me it seems slightly tacky that two different tombs side by side would

have identical angels on their roofs.

Of course, it might have been an intentional plan by two families who

shared some common heritage or neighborhood or something.

I try not to judge. I just report.

Alejandro Sartori's sculptural group for the

Bustinza-Larrechea tomb (c.1890) is pleasant enough . . .

but then on closer examination, the pointing angel seems a bit

alarmed . . .

maybe because his pointing finger has been reattached . . . with tape!

Alejandro Sartori also made this sculpture for the Schoen Family

tomb in 1896.

Unfortunately, he probably should have faced it the other way, given

the new (black) building next door basically blocking its view.

Urban renewal. Whatchagonnado?

Catamarca, 28-30 September 2019

Catamarca is another Argentine mid-sized city that is even

farther away from everything than Rosario.

And it was hot, at least while I was there.

And I was there too long.

With one flight per day from the Catamarca airport,

Aerolineas Argentinas cancelled my exit flight at the last minute because

of a pilot strike. Aaaaargh.

On the way into town from the airport, suddenly this sculpture seemed to appear out of nowhere, at the front wall of the local Escuela Pública de Orfebrería - School of Goldsmithing. Other than what-you-see-is-what-you-get, I know nothing about it, except that the guy coming through the wall and the guy sitting on the anvil on top of the wall weren't there when the Google Street™ camera truck came by in October of last year. (Click here to see what I mean.)

The dogs of Catamarca are a privileged class.

This doggy is not dead - s/he's resting, in front of the main door

of the Cathedral.

Earlier, three dogs wandered into the Cathedral - without

genuflecting, I have to say - looked around, then wandered out.

Once, when I was in a library asking for information about the city's

sculptures, a doggy sauntered in and nobody batted an eye.

They don't seem to be looking for food - I learned later than people

in the community routinely provide food for any dog that might be

hungry - and they are gentle as they can be - almost indifferent - rarely

barking and never fighting.

They are, quite simply, equal members of the community.

And there's lots of 'em. Remarkable.

If this is an example of the civic sculpture of Catamarca, then the

situation is pathetic.

OK, so it's now 30 years old, having been inaugurated by the

Rotary Club in 1979, but the sign says it was restored in 2014.

It looks like a first attempt in a junior-high pottery class that

was abandoned because they ran out of cement.

(I'm sorry, but a pleasant square in front of the Cathedral

deserves better artwork.)

I found pictures of this elegant monument on the Web before my trip,

and I considered coming to see it - and to learn it's

creation date, and perhaps see other sculptures in the same Cemetery.

As it turned out, I was not able to pin down a date, although it

apparently was there within a year or two of the Cemetery's opening in

1898. (It's main occupant, Don Benigno Castro had died more than

30 years earlier; this became the tomb for his family once the

Cemetery was ready.) I also found, once I visited, that it is one of

only a handful (less than 5) classic funerary

sculptures in the whole Cemetery.

Still, it was worth the visit to get my own photographs, which were

essential once I learned the work was sculpted by Achille Canessa

(1856-1905) of Genova.

Canessa's angel on the

Giovanni DeVoto Family tomb (1912)

in Genova's Staglieno Cemetery is

very similar (but, to Canessa's credit, not identical).