Montevideo, Bolivia, Lima (briefly), Quito

19 October - 2 November 2018

19 October - 2 November 2018

photos by G.P. Jones using Nikon D3400 digital camera,

except where noted

Montevideo, 19-23 October 2018

Welcome to Montevideo.

Apparently the locals need a reminder that

Tourists = Money

therefore

Tourists = Friends.

As for me, I felt welcome.

There is basically only one Montevideo travel picture, and it's always some version of this - the Plaza Independencia, with the rear end of Gral. Artigas's horse and the impressive Palacio Salvo tower

Uruguay's connection with Italy is never far from view, from the cemeteries (as we'll see later) to the public artwork. This replica of Michelangelo's David stands in front of the civic building known as the "Intendencia" on Avenida 18 de Julio, Montevideo's most important street.

The Intendencia David is not the only guy in town, as other artists take similar inspiration for their work. This is a creation of Carlos Darío Fierro (2012), on display - and likely also for sale - in a colonnade at the edge of the Plaza Independencia.

The city is full of a wide variety of public sculpture, from the predictable equestrian statues to the unusual visions of more recent artists. The work of José Belloni (1882-1965) is everywhere in Montevideo. This complex installation known as La Diligencia (1952) depicts a team of horses pulling a carriage out of the mud. It is at the edge of Parque Prado, Avenida Agraciada y Avenida Delmira Agustini.

This monument (1932/1954) portrays Spain as the "Madre Patria", even though Uruguay was part of the Empire of Brazil before its independence in 1825. The bronze and marble figures are by José Clará Ayats. It is found at the Plaza de Isabel la Católica, in the Avenida Libertador Brigadier General Juan Antonio Lavalleja.

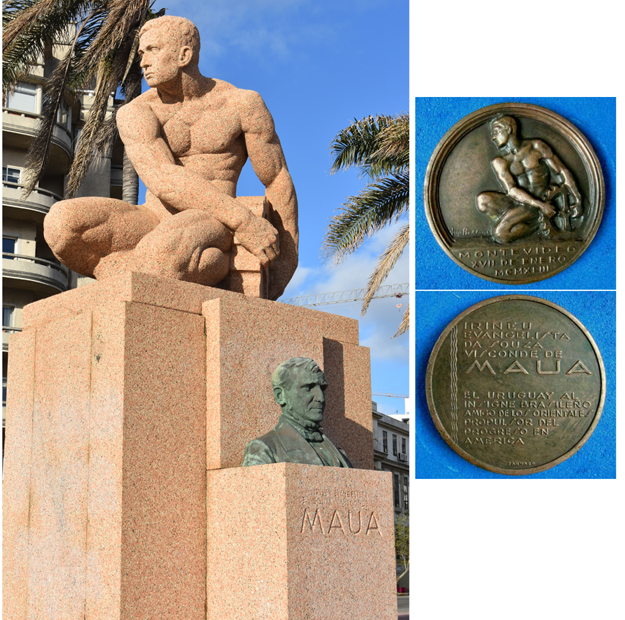

Along the shores of the Rio de la Plata is another work by José Belloni, his Monumento a Vizconde de Mauá (1943). The light orange colour of the granite is strikingly different from most other monuments in the city. Belloni also designed a commemorative medal for the unveiling of the monument. The bronze bust of Mauá is by Rodolfo Bernardelli (1852-1931).

At each of the four corners of the Palacio Legislativo are large sculptures (one Web site describes them as 'Rodinesque' - I can see that!) by Italian sculptor Giannino Castiglioni (1884-1971). They were made in 1923, then re-cast in the 1970s for installation here. This work is La ley [Law]. The others depict El trabajo [Work], La ciencia [Science] and La justicia [Justice].

While visiting the grounds of the Palacio Legislativo, I noticed a group of young people rehearsing a dance or drill-team routine in front of the building. I stopped to take a picture, and the man on the ladder (left) semi-politely informed me that this was a "private" activity, no photographs allowed. I'm afraid I just laughed at him, as his group was in one of the most wide-open, public settings in Montevideo, and took my picture (with him included) anyway.

In 2012, South Korean artist Yoo Young-ho (born 1965) gave one of his Greetingman sculptures as a gesture of good will to Montevideo. The man (with modesty-altered genitalia) is bowing politely in characteristic Asian fashion. According to the artist, he is blue(-ish) so that no ethnicity can be assigned to him, and naked to symbolise all people - clothing could easily be interpreted as an indication of nationality or social status. (This representation of the 'universal human' is, of course, a basic rationale for nudity in art - contrary to prudish Conservative gut-reactions.)

Birds have found places in these bas-reliefs by Edmundo Prati (1889-1970) to build their mud nests. They can be seen above the man's left hand, and on the woman's left shoulder. These figures are on either side of the pedestal holding the equestrian bronze of José de San Martín, at Avenida Agraciada esq. Gral. Francisco Urdaneta.

The sign speaks for itself, as long as you understand that they primarily serve drinks.

Plumbing in Uruguay, and much of South America, is easily clogged. This sign in a restaurant 'convenience' cleverly reminds the patron that he (yes, it was the men's room!) wouldn't clog the toilets at home, and for the moment, "This is your [home] toilet."

Instituto de Enseñanza Secundaria No.6 Francisco Bauza advertises its committment to diversity. Bravo.

Strong words, not to mention BIG graffiti. I presume the fact that it's in English fools the cops into thinking it's just harmless street art.

Street art - not just scrawled graffiti - is very popular in all the countries I visited, and much of it is done by apparently accomplished artists.

Some street art is subtle, or just pretty - other pieces are more direct.

I found this wall a bit hard to decipher. I imagine the image of the woman is separate from the painting of the two men, but the meaning of either grouping eludes me.

This wall truly surprised me. I wouldn't have expected to see a reference to a 1902 French film (George Meliés's Le voyage dans la lune [A Trip to the Moon]) as street art in South America.

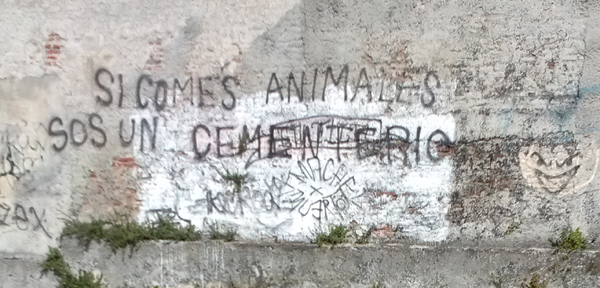

Some graffiti knows where it sits (so to speak). This warning [English: "If you eat animals, you are a cemetery"] is on the outer wall of the Cementerio Central in Montevideo.

There is a fair amount of anti-meat-eating graffiti here, such as this clever (?) split screen of a doggie and a future steak dinner. I noticed this type of graffiti also in Buenos Aires more than a decade ago.

[image added 20 January 2019]: A couple of weeks ago, I discovered this interesting contrast to the anti-meat graffiti just above, at a restaurant here in California (USA). Some difference, eh?

I'm including this picture solely because of the apprehensive (to say the least) expression on the face of the kid on the right. As for the guy on the left, it looks like the picture was taken when he had the back and sides trimmed, but the barber hadn't gotten to the top as yet.

Here begins an important part of this journey, as with most of my trips of the past four or five years - a visit to look at funerary art, aka cemetery sculpture, this time in the Cementerio del Buceo in the suburbs (as it were) of Montevideo.

This mausoleum is not alone in using Egyptian themes in its design. It also has a feature I've not seen before - the writing on the front may be Arabic, or even hieroglyph, and the date - 3-9-37 - is written backward, as if a mirror were needed to read it.

Tourist photographers are not welcomed with open arms in this cemetery, nor are they merely ignored as is the case in most other parts of the world. In order to photograph monuments, one must register at the Office - they take a photocopy of your passport, even! - and promise not to photograph the names on the tombs, mausolea and monuments. It wasn't easy to comply - often the name(s) of the deceased and/or their families are found in the middle of an otherwise interesting sculpture or architecture. I've included here only pictures like this one which emphasise the design without highlighting the 'inhabitants'.

I've always known that the Monteverde angel (the original being the exquisite marble on the Oneto tomb [1882] at Staglieno in Genova) has been copied in cemeteries around the world. Still, I was a bit surprised to find that there was at least one copy, sometimes more, in the cemeteries of every one of the four cities I visited, including this one in the Buceo.

Moving now to the Cementerio Central in the Ciudad Vieja (Old City) of Montevideo, we can continue the theme of sculpture 'borrowed' from famous Italian art. The statue on this grave is a near-exact copy of The Martyrdom of Saint Cecilia in the Chiesa di Santa Cecilia, Trastevere, Roma, sculpted around 1599 by Stefano Maderno (1576-1636).

Copying a famous grave sculpture is both understandable and acceptable, of course, as long as a sculptor doesn't claim the work is his or her original. The statue atop this pedestal is a copy of Bimbo inginocchiato orante [Child Kneeling in Prayer] (1830c.) by Luigi Pampaloni (1791-1847) in the Galleria d'Arte Moderna in Genova/Nervi, Italy. It is a very popular image seen in cemeteries around the world.

We've already seen inside the Cementerio Central in this travelblog. This is the impressive gate through which one enters the grounds. (All the following cemetery photographs in Montevideo are from Cementerio Central.)

One of the first things the visitor will notice is the noisy parrots that almost seem to be guarding the place. At least they sound annoyed that anyone else is intruding on their territory. They are the same kind of green parrots that used to visit a tree near the apartment I used to live in; the owner of the building, who had lived on that property since her birth in 1905, told me that the same parrots had been coming back once or twice a month for forty (40) years!

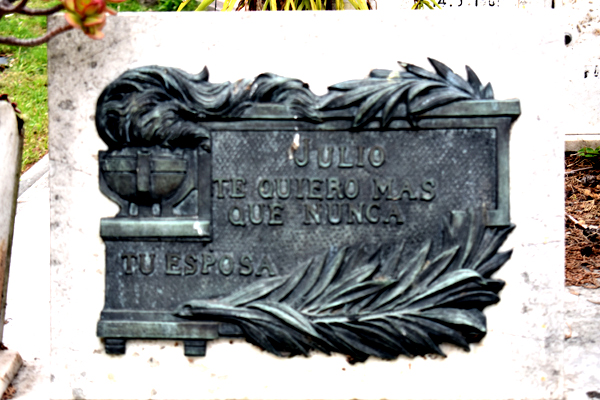

This plaque constitutes a mixed message, no doubt unintentional: a wife tells Julio that - now that he's gone - she loves him more than ever!

The angel with the downturned torch (a symbol of life at its end) is an image that fascinates me, full of meaning and emotion and part of a history several millennia in the making. Such an angel often is referred to as the "Angel of Death", but this is misleading, since the same term often conjures up images of the "Grim Reaper". Actually, the angel with the downturned "torch of life" is the angel who assists with death, who guides the deceased into the next life, then stays behind to mourn. I will refer to this figure as the "Angel for Death" (until I think of a better term).

This sarcophagus for Colonel Bernabé Rivera (1795-1832) is said to be the oldest grave in the Cementerio Central. (I couldn't verify that on this visit.) All four sides of the plinth are covered with inscriptions that tell the story of how Rivera participated in the massacre of indigenous people in the battle of Salsipuedes (1831), and a year later was captured by Guarani 'Indians', killed and dismembered. It is unclear whether Rivera is regarded today as a hero or not, but it is significant that Uruguay is known as the only country in the Americas with no indigenous population.

This tomb for José Casalia (1896) features a Resurrection Angel blowing a trumpet.

Just a few feet away, the monument for Juan Peirano and Antonia F. de Peirano (1913) has the same overall character, and also features an angel trumpeter.

The style used for the tomb of Alejandro Beisso (1854-1936) is clearly more modern than most of the other artwork at this cemetery.

The miniature detail around the base of this tomb for Gral. Miguel Navajas (1839-1903) is nothing short of astounding. Felice Morelli (1857-1922) was the sculptor.

Another interesting theme in European cemetery sculpture is the angel writing on the tomb itself, as seen here in the monument for Bartolomé Scarone (died 1878). To be fair, maybe the angel is only pointing at Scarone's date here, but the idea is the same.

This angel is unquestionably writing, stylus in hand, on the tomb of Alejandro Chucarro (1790-1884), as sculpted by Juan Azzarini (1853-1924).

The marble figures on this grave for Alciro Sanguinetti (died 1897) were sculpted in Genova in 1901 by Santo Saccomanno (1833-1914), whose work is well-represented in the Cemetery of Staglieno in that city.

Here the angel on the grave of the Rossell y Rius family has a curious star-shaped figure on his head, apparently part of a cap he is wearing.

(NOTE: in a Web search, several images showed up of angels with stars on their heads - not always with any cap or hat - but no definitive explanation of the star's meaning. As is all-too-common these days on the Internet, a number of people offered their [uninformed] opinions, with one blogger suggesting "It is a stamp of approval from God and baby Jesus." Without dignifying that opinion, or any other, I have to leave it unsolved at this point.)

I can't be the only [English-speaking] person who sees this grave-name as "STORAGE", can I? Of course, it's "STORACE". Still, the near-possibility of the double meaning is tempting.

Many of the graves here have added plaques, sometimes for additional burials in a family plot, and sometimes added by individuals or groups to commemorate the interred person(s). (The term in Spanish is homenaje - homage.) The business of supplying designs for these plaques is not always an original enterprise. Here, two side-by-side graves (presumably for different families) have plaques with the same designs.

I'm posting this without comment, except to say 1) I can't resist, and 2) I mean absolutely no disrespect.

Cultural differences made me do it.

I mentioned the homenaje plaques above. If the plaque-to-grave ratio is any indication, this person was very well-regarded, indeed.

Some monuments or sculptures are allowed to be covered with ivy. (See below for a much greener example.) This is what happens when the encroaching plant dies, and the vines are left in place.

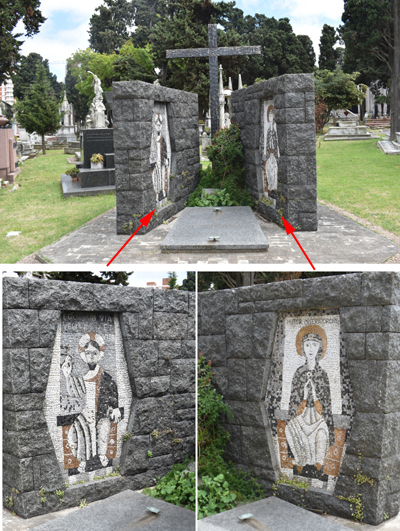

Mosaics, especially on outdoor monuments, are quite rare in cemetery art. This monument for the Familia Zerbino features images of Jesus [the Latin inscription translates to "I am the way, the truth, and the life"] and St Mary ["Mater Misericordiae" = "Mother of Mercy"].

This sculpture, unusual for a cemetery, is the work of another Italian sculptor. The grave bears the signature, "E[nrico]. Butti, Milano". Butti (1847-1932) created this work. Il Minatore, around 1889. The marble original is in the Museo Enrico Butti, Viggiù, Italy, and another version in bronze, Minatore con lanterna is in the Nordfriedhof in Dusseldorf.

This tiny mourner is not quite an "Angel for Death" as he has no wings, but he is holding a downturned 'Torch of Life'. Being so small, he is reminiscent of the original Thanatos angel, namely Cupid/Eros. As strange as that seems, Cupid/Eros is seen on ancient Roman coins with the downturned torch, an image which evolved over millennia to the Thanatos angel (German: Trauernden Engel or Ruhenden Engel) seen in the last few centuries.

This monument, created in 1910 by Giovanni del Vecchio, bears the inscriptions, "To the dedicated propagandist [proponent] of Uruguayan Fraternity . . ." and "Strength in Unity". It pays tribute to Domingo Aramburú (1843-1902), an advocate of "concordia civica", who wrote a book in 1898 titled La fraternidad uruguaya.

This captivating figure was the main focus of my visit to Montevideo. There are several photos of him - some completely without the green overgrowth - but no-one mentioned the name of the grave he sits on, and it was unclear just what he is doing with his right hand. A wider view of the grave reveals the deceased is Martín Ybarra. (No further details on him or his family could be found.) What the young angel is doing there is still a mystery. On close examination (myself, in person), I could find no evidence that he is writing on the stone, or picking up a bug or butterfly, or any other recognisable activity. That's OK. A cemetery should have some unsolved mysteries, after all.

Back on the street in Montevideo, the buildings continue to be impressive. It seemed to me, no matter where in the city I went, that no two buildings were exactly the same (unlike our cookie-cutter architecture here in America and Britain). And lotsa buildings were made from brick, with inventive designs and details, like this.

Art Deco and Streamline Moderne architecture is very popular here, as this and the next few pictures show.

This building stands at Paraguay, 1079, near the corner of Durazno.

Avenida Agraciada, 3265

a closer view of Avenida Agraciada, 3265, showing Deco details

details on the building at Avenida Agraciada, 2487.

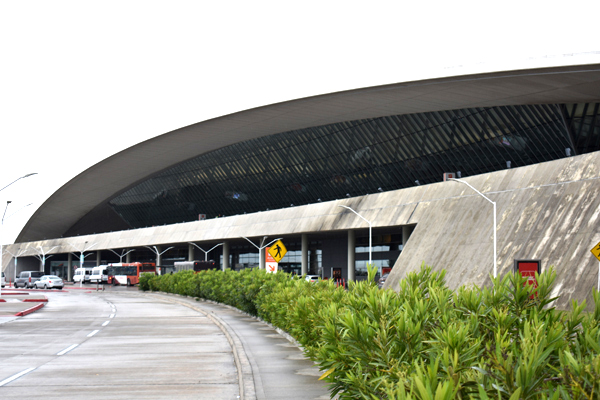

Terminal Building, Aeropuerto Carrasco (MVD), Montevideo

La Paz, 24-29 October 2018

Suddenly, from the sea-level charm and grace of Montevideo, we are now more than 2 miles up (3,650 m, 12,000 ft), even higher on the El Alto plain (where the airport is). This view from my hotel room is in the La Paz "valley", with the El Alto ridge in the background.

(NOTE: This is a PANORAMA picture - scroll to right or enlarge your browser to see it all.)

The median decoration seen in the panorama above is mostly grass and small plants. This is the other side of that median garden. (The Hotel Monte Carlo balcony, from which the panorama picture was shot, is marked with the yellow arrow at upper left.)

Back on my third-floor balcony, I had a great view of the many parades passing by during the week-long celebration of Dia de Todos los Santos.

Bolivia is all about colour. Later, you'll see a flag that celebrates the culture's pre-Inca reverence for the seven colours of the rainbow, which indigenous Bolivians proudly display whenever they can.

To me, the most interesting indigenous Bolivians are the Aymara women. Their styles of dress vary, but the common denominator seems to be these bowler hats. Meaning no disrespect, I just can't see these without thinking of the great Laurel and Hardy.

Bolivia does not seem to be a wealthy country - though there is little obvious poverty, either. On the other hand, their cable-car system, known as Mi Teleférico, would be remarkable in any more developed nation. More than just a single line from a valley to a high observation point (such as the tourist-attraction cable-cars in Cape Town and Bogotá, for example), this is a transportation network already, with more lines being constructed.

The Teleférico Linea Roja, seen here, takes the rider to the 16 de Julio station at the top of the El Alto ridge.

The view from the 16 de Julio station is magnificent. Most of the buildings in La Paz are made of reddish-brown bricks, giving the city a certain uniformity that almost looks like a carpet of homes.

(NOTE: This is a PANORAMA picture - scroll to right or enlarge your browser to see it all.)

Considering the population of México D.F. is over 20 million, I thought La Paz might be similarly populated. I could barely believe the taxi driver who told me that La Paz itself has around 1 million, with another 1 million or so in the El Alto area. It turns out he was right.

Along the Teleférico route, large street-art pieces often can be seen.

This building, seen from the Cementerio General, is unusual in its design and colour. The plain-brick buildings in the distance to the right are more typical.

Here is the La Paz version of the Monteverde angel (seen in every city on this four-nation tour, as noted above). The deceased, who died in 1911, is honored on the statue's base by the tribute, "Fuiste el angel de nuestro hogar" - "You were the angel of our home."

The mausoleum for the Perez Velasco family (1910) is probably the most detailed artwork in the Cementerio General in La Paz.

The sculptures on the Perez Velasco mausoleum are Mercurio (left) and la Virgen con el Niño (right). Wait - take a look at Mercurio - he's portrayed as a woman! I suppose we can file that under 'artistic licence' (though it might be more appropriate under 'artistic naïvete').

José Manuel Pando (1849-1917) was president of Bolivia, 1899-1904. More than 30 years after his death, his mausoleum was sculpted by Hugo Almaraz (1910-1980) in 1950. This probably accounts for the Art Deco style of the bas-reliefs.

By far, most of the burials in the Cementerio General in La Paz are in niches such as these. Showing a wall of the departed, backed by a hillside of the still-living, just seemed irresistible.

The niches here are unlike any I've ever seen before. Most of them have doors with locks, typically with glass (or plexiglass) which makes the contents visible. Inside are figurines and flowers, and also food and drink, including glasses of water and tiny bottles of brand-name beverages.

Some niches include liquor and packaged snacks.

This niche contains a local energy drink (!) called Coka Quina ('no retornable', according to the yellow and red label on the bottle), and the small figure at the bottom left moves its 'leaves' up and down, and its flower back and forth. (I'm guessing it's solar-powered.)

Well, this at last solves a mystery and a persistent urban legend. So this is where he is!

When I came to the Mausoleo de la Familia Escobari Cusicanqui, it was being cleaned either by cemetery workers or volunteers. Such workers were all over the cemetery the day I was there, and the results of their work was obvious. There was even an artist there, painting a new mural on one of the walls. (Other cities should take such pride in the legacy represented by their cemeteries.)

My only out-of-town trip was a visit to the ancient ruins at Tiahuanaco (also called Tiwanaku), about 75 km (47 very bumpy miles) West of La Paz, near the Southern shores of Lake Titicaca. The presumed age of the Tiahuanaco settlement has ranged from 11,000 years ago to the now-accepted estimate of about 2,000 years ago. As such it is much older than Machu Picchu, but not nearly as interesting nor mystical.

The area of Tiahuanaco where people lived is now covered by the modern town (where people still live). The ruins (shown here) represent the ceremonial areas near the population centre. This figure is known as Estela Fraile, or Monolito Fraile. An 'estela' is a vertical stone, often with carvings; 'Fraile' - 'Friar' - was the name given to it by Spanish missionaries much later.

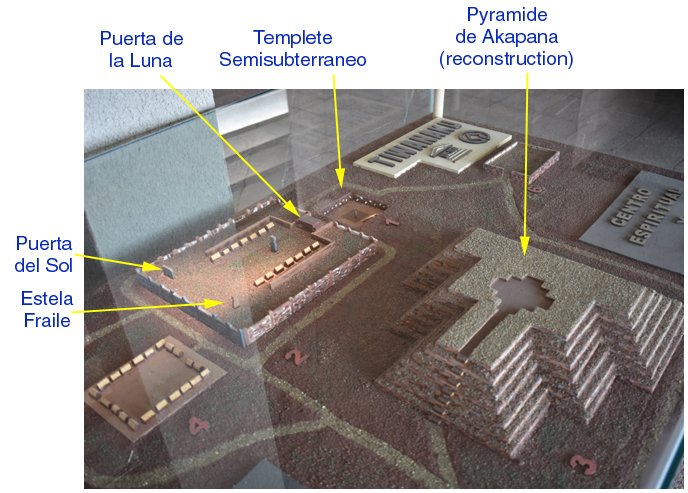

This mound was once a well-defined pyramid (see the model below), known as Piramide Akapana.

The Puerta del Sol, among other features of the site, establishes this culture as sun- and moon-worshipers, as were many ancient cultures. Its position relative to the Equinoxes and Solstices is reminiscent of Stonehenge, for example.

The 'walls' of the Templete Semisubterráneo are lined with representations of heads/faces, probably representations of various races of people who lived at, or visited, Tiahuanaco. Beyond the sunken rectangle are the walls of the main Kalasasaya Temple, including the Puerta de la Luna in the centre.

A model of Tiahuanaco's ceremonial layout in the local museum.

Pumapunku (Door of the Puma) is another temple complex, not as well preserved nor excavated as the sites shown above, roughly half a mile SouthWest of the Kalasasaya Temple.

La Paz, like many cities, has its 'flatiron'-type buildings, placed in narrow corners of intersecting streets. This one is perched on the edge of a steep cliff, but then, so is much of La Paz, to be honest.

The Plaza Murillo is the physical and social centre of La Paz, designated as 'kilómetro cero' ('kilometre zero'), the point from which all distances in Bolivia are measured. A bronze plaque marks the exact spot. The building at the left is the Cathedral Basilica of Our Lady of Peace.

In former times, the Plaza was well-known as a site for public hangings. Today, its main feature is lots of pigeons, probably because corn such as this is sold around the square.

The Bolivian national flag marks a public building.

Multiple flags fly in front of the Government Palace, the residence of Bolivia's president.

The tomb of Andrés de Santa Cruz (1792-1865), part of the Cathedral building, is open to the street and guarded by soldiers. De Santa Cruz was president of Perú (1827) as well as president of Bolivia (1829-1839).

Around the Plaza Murillo stand eight graceful female sculptures representing the seasons, as well as Painting, Architecture, Music, and this statue for Sculpture. Ironically, this is the only one of the eight with any major damage. Srta. Sculpture is missing an arm.

This is the Wiphala flag, the standard that represents the seven colours of the rainbow, an important symbol of Bolivia's indigenous people going back to the residents of Tihuanaco (discussed above). To the right of the two flags is the famous backward clock, on the façade of the Congress Building. The clock is a relatively recent quirk, reversed in 2014 reportedly to reflect Bolivia's position in the Southern hemisphere (i.e., the 'reverse' of the Northern hemisphere) and to encourage Bolivians to "question established norms and think creatively" (according to the BBC).

Lima, 30 October 2018

NOTE: this visit to Lima was carried out during a 10-hour layover at Lima airport, on the way from La Paz to Quito; the only purpose was to visit the Cementerio Presbítero Matías Maestro, though I was also able to spend an hour or so at Eugenio Baroni's remarkable monument to Jorge Chavez.

Street art, probably loaded with symbolism, seen along Jirón Ancash, across from the Cemetery entrance.

The entrance to Cementerio Presbítero Matías Maestro, across from the street art (noted above).

One enters the Cementerio by an overpass, offering this birds-eye.

The Cementerio is also designated as a Museo. At one 'axis' of its pathways is this gazebo . . .

at another 'axis' this Panteón, or civic mausoleum, dating from 1908.

This cemetery has two versions of the Monteverde angel. This one is a copy.

This version of the Monteverde angel is slightly modified, with finger-to-lip encouraging silence (yet another feature found in a number of Italian funerary sculptures).

Grief is clearly evident in this sculpture enveloping the small tomb of Juan I. Elguera and Dammert Elguera (or perhaps one individual named Juan I. Elguera Dammert Elguera). It is not clear from the inscription, but an official catalog of the Cementerio dates the monument as 1975.

The familiar "Angel for Death" motif appears on both sides of the mausoleum of José Manuel Tirado (died 1855), along with another angel figure, also repeated on both sides.

It is rare, but sometimes the "Angel for Death" figure holding a downturned torch is sculpted as female, as for this tomb of Francisca Yrinarren de Soria (1837-1885). When the Angel figure is female, it is virtually always the case that the deceased also is female.

After finding some beautiful photographs of this grieving "Angel for Death" (on the left) on the Web, my need to identify the tomb became my main motivation for visiting this cemetery. It is a small sarcophagus, with an important burial for Jral. de Division Don José Maria Plaza y Moncada (1792-1857), according to the inscription, "one of the champions of South American independence." I placed the flowers there myself.

Here above the tomb of Don Mariano Necochea (1790-1849), an "Angel for Death" mourns while another angel places a wreath.

Here a crowned woman attends, while a small angel places a floral wreath on a symbolic urn. This monument for the Familia Garcia (1872) was made by the Genovese sculptor Giovanni Battista Cevasco (1814-1891), well-known in Italian cemeteries.

The mausoleum of Oscar R. Benavides (1876-1945) is massive, befitting his stature as soldier, diplomat and twice president of Perú. He is quoted as saying, "Para mis amigos todo, para mis enemigos la ley" ["For my friends, everything; for my enemies, the law"].

Mausoleo para la Familia Klauer

Mausoleo para la Familia Fumagalli is a combination of several styles of art.

Mausoleo para la Familia Julio de la Piedra (1935)

Tumba al Gran Mariscal Don Agustín Gamarra (1785-1841), yet another president of Perú buried in this cemetery.

Tumba Dr Juan de Dios Salazar y Oyarzábal (1875-1923)

The intricate sarcophagus of Eduardo Juan de Habich (1835-1909) is the work of the French/Italian sculptor (resident of Ecuador), Carlos Libero Valente Perrón (1859-1922).

Quito, 30 October - 2 November 2018

The Hotel Casa Montero is a renovation of a colonial home, located steps away from Iglesia San Francisco. The lobby is spacious, the rooms comfortable, and the price is right - around US$45.- per night . . .

. . . including full breakfast in this pleasant room looking out on Quito's iconic El Panecillo hill.

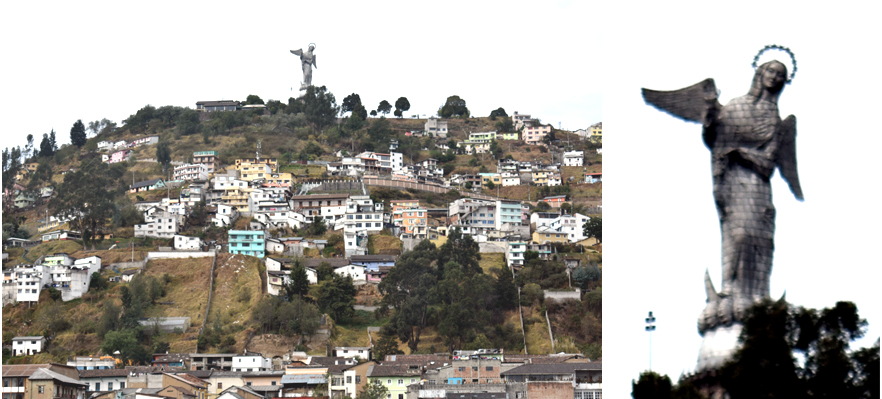

Atop El Panecillo is Quito's answer to Rio de Janeiro's Cristo Redentor and similar knockoffs and imitations sitting on hill and mountain tops in many other places around the world. The problem with this statue of the Virgin Mother is that, unless you're close enough to see the detail, it looks 'broken' - at least to me. I tried to deny it for days, but in the end I had to admit she just looked deformed. I came to think of her as Quasi-Mary - with no disrespect to the Holy Mother herself, of course, just as a comment on the sculptor's questionable vision. (I should regret the unforgivable pun between Quasi-Mary and Our Lady [Notre Dame!] but I don't. I may spend eternity somewhere other than I had hoped!)

This café also has a religious message: God does not die (probably comparable to the English phrase, "God is not dead"). I presume, then, the food is pretty good here.

On the other hand, here we have Sloppy Coffee (conveniently) next door to a Medical office.

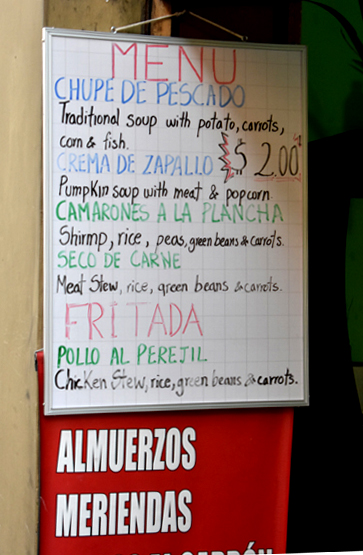

This sign still makes me wonder whether the altitude in Quito was making me hallucinate. Consider the second entry on the menu, Crema de Zapallo: Pumpkin soup (so far, so good) with meat (OK) and popcorn???

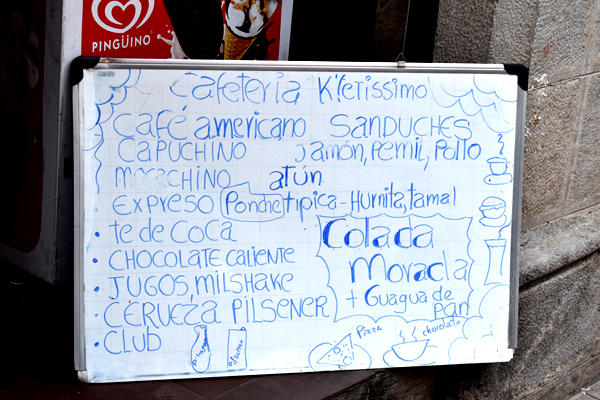

Another sign that gave me pause, mostly for the questionable spelling of most of the non-Spanish words. I tried to point out to the proprietor that "Capuchino" was a variety of monkey. The conversation went something like this:

Yo: Esto es un mono.

El: Sí.

Yo: Esto es un mono.

El: Sí.

And so forth. I gave up and ordered an expreso [sic]. I couldn't risk having one of his "sanduches".

The Basílica del Voto Nacional looks ancient, but isn't, having been begun in 1887 and consecrated in 1988 by Pope (now Saint) John Paul II.

Given the solid look of the rest of the building, this steeple, which is over the main crossing of the nave, looks unfinished to me.

The Basilica is technically unfinished. Local legend maintains that if and when the church is finished,

the end of the world will come.

The two sides of this bronze door were open, so I photographed them separately then put them back together, so to speak. The bronze reliefs on the great doors are signed by sculptor Agustín de la Herrán (born 1932), and were completed in 1984, just before the building's consecration. De la Herrán, by the way, is the sculptor who created the abovementioned statue of the Virgin Mary on El Panecillo hill, using Bernardo de Legarda's (1700c.-1773) 1734 original miniature (30cm) Virgen de Quito as the model.

The Basilica's rose window.

This Basilica's 'gargoyles' are images of local Ecuadoran animals, such as sloths, condors, armadillos, Galapagos giant tortoises, and iguanas.

According to this multi-lingual sign (bottom row, middle and right),

RIESGO DE CAIDA POR LA VENTANA means BEWARE RISK OF FALL, and

MANTENGA A SUS NIÑOS CON USTED means BEWARE RISK OF FALL.

¿En serio?

The guide on this tour bus directed our attention to these mountains, which he called a "volcano complex".

Now he tells us!

This guy on the left is beginning to realise that it may already be too late!

Now, to the Cementerio San Diego, one of the reasons for travelling to Quito.

Just inside the gate, the Familia Endara mausoleum starts us off with an unusual design for a tomb.

This block of niches, despite the sign, is not what you might think.

This block of niches is REALLY not what you might think.

The monument over the Tumba Familia Mercado is a structure right out of the ruins of Imperial Rome.

Ecuador's national flag is a part of this monument for Dr Aurelio Mosquera Narváez (1883-1939), president of the Republic during the last year of his life.

This is one of the more unusual cemetery installations I've ever seen on my travels - a sport ground with a relatively new net stretched across. It seems to be an Ecua-volley court, though there was no-one around who could verify this. Ecua-volley (Ecuavoley to Quitonians) is a local form of volleyball. Yes, it was dead center (sorry) in the cemetery, with graves and mausolea all around. But who's playing?

The high-relief bronze on this tomb for the brothers Virgilio and Honorio Jaramillo (1930c.) was executed by Luis Mideros Almeida (1898-1973).

Art Deco influences can be seen in this mausoleum for the Familia Lavalle Cardenas (1941).

This highly stylised relief on the grave of José Peralta (1937) is relatively small, and is set in a rough stone. Other reliefs are on other sides of the stone.

Perhaps the most commanding figure in Cementerio San Diego is this angel, sitting on a high throne surveying all before him. The monument was designed for the Familia Palacios Alvarado around 1905 by Pedro Durini Cáceres (1882-1912), newly arrived in Quito from Europe (via Lima), and his associate, sculptor Adriático Froli (1858-1925). Note the position of the angel's left hand (enlargement), the early-Christian coded greeting seen in sculptures and paintings on previous travels. Apparently, the angel originally had a silver sword in his right hand, now lost due to a robbery.

[A sculpture nearly identical to this one, though with a different facial expression, sits sideways on a pedestal (not a throne, as here) over the tomb of António Augusto de Aguiar (1838-1887), in the Cemiterio dos Prazeres in Lisbon. It was sculpted by J.P. Lima Santos, still holds a sword, and his left hand, supporting the sword, only has an index finger extended.]

This view makes it obvious just how prominent our "Angel with(out) a sword" is.

Like many other capital cities, Quito's central plaza has a monument at its centre, and important buildings around the square. It is known formally as the Plaza de la Independencia, and locally as Plaza Grande.

The lion at the base of the Monument to the Independence Heroes of 1809 is either extremely fierce, or very hungry. (Or both?)

These cherubs, inside the Iglesia de San Francisco, seem to be protecting their modesty, except for the exhibitionist at the upper left.

Arguably the most ornate church in Quito is the Iglesia de la Compañia de Jesus, built between 1605 and 1765. For certain festivals, the church is illuminated in a blaze of colours.

Entering the church, one is overwhelmed by one feature: gold. It seems that every surface - ceiling, pillars, altars, doors - everything - is covered in gold. (This is a brochure photograph; tourists are not allowed to take pictures, except in the crypts - see below.)

For a fee, visitors can tour the crypts. The Cripta Principal under the altar is accessed by regular stairways. This crypt, just in front of the Retablo de San José at the right side of the main church, is accessed through nothing more than a hole in the floor.

The crypt is very small, and no longer used for burials. The skull seen here is "just for atmosphere".

Evening in Quito gives us a chance to say buenas noches to Quasi-Mary.