The Grand Tour of Monumental Cemeteries in

Italy and Austria, with a "Bonus" trip to Berlin

22 September to 17 October 2016

Italy and Austria, with a "Bonus" trip to Berlin

22 September to 17 October 2016

photos by G.P. Jones using Nikon Coolpix L830 digital

camera, except where noted

Roadmap (conceptual and otherwise)

The wealthy, or pretentious (or both) of XIXth-century Europe decided that it was not just Royalty who could leave their mark by grand memorials, so - if they were so inclined and so endowed - they hired the great artists of the time to create monuments to be placed on their graves in the great suburban cemeteries that were established after Napoleon's 1804 Edict of Saint-Cloud that burials could no longer take place within city walls nor in churchyards. The result, in most larger cities, was nothing less than enormous sculpture galleries, in fact, Europe's largest outdoor museums.

The Grand Tour of Monumental Cemeteries was a sort of specialized version of the upper-class Grand Tour tradition in which young aristocrats spent months, sometimes years after their formal education, seeing Western Culture in person, an odyssey not for the faint of heart nor wallet. But I digress (as usual).

My interest in visiting these Monumental Cemeteries began two years ago when I stopped by the Cimitero Monumentale di Staglieno in Genova to see, in person, a sculpture that had captivated me when I ran across it in a book of postcards I picked up at a yard sale in my local community. No kidding. (You can see the photographs I posted from that trip in 2014 elsewhere on this Web site.)

I was literally stunned by the beauty, not to mention the emotion and history and technique, of the sculptures at Staglieno. The fact that a century or more has left many of the art works dusty, in some cases even broken or otherwise vandalized, was only slightly discouraging, especially in light of the fact that there exist a number of organizations and individuals dedicated to restoration and maintenance of these treasures. (More about that as we go along.) When I learned on further Web crawling that there existed similar "museums" (i.e., monumental cemeteries) in most major European cities, I decided to see what they might have to offer.

In any systematic (some would say obsessive-compulsive) observation of an artistic phenomenon like cemetery sculpture, themes begin to emerge, even to visitors like me who are not art historians (not even close). The themes that most interested me were as follows (I will refer to them throughout the guided tour below):

- the Guiding Angel (sometimes viewed as the Guardian Angel; details below)

- monuments designed particularly to evoke emotion (heartbreakers)

- characteristic "styles" of each cemetery

-

(For example, it seemed the layout and terrain of some cemeteries

seemed to mirror the terrain of the cities in which they were found:

Staglieno is built on the side of a hill, rather like Genova itself;

the Campo Verano has several hills within its walls, somewhat like

the hills of its host city, Roma; the Cimitero Monumentale di Milano

is pretty much flat, as is Milano; and so forth; or maybe it's just me)

(The contents [so to speak] of the cemeteries also tended to contribute to a sense of individuality. In Italy, some had a lot more inscriptions in Latin, while others were primarily Italian. For some reason unknown to me, but probably obvious to the city's residents, Milano's cemetery had many more images of St John the Baptist (San Giovanni) on its graves than any other city I visited. And all of a sudden, as it were, when I arrived in Vienna (Wien), I began to see numerous variations of the "Ruhenden Engel" ("Grieving Angel") image. (Again, I'll revisit these ideas below.) - restoration efforts evident in almost every cemetery

- slogans used on some graves, some hopeful, some dreadful, and some even contradictory

- the sculptures correspond to artistic styles: Classical, Romantic, Symbolism, Realism, Modernism, for example, (remember, I'm not an Art Historian)

- the gravestones themselves, especially the mausolea and chapels constructed by the more wealthy families, correspond to architectural styles: Classical, Gothic, Beaux-Arts, Art Deco, Post-Modern. (N.B.: I'm not an Architecture scholar, either!)

- Angels - obviously quite common in cemetery sculpture, and almost always adolescent or young adult in appearance - tend to be male prior to the XXth century and female thereafter. (Note that all Biblical angels that I've ever heard about are male: Gabriel, Michael, Ariel, &c., &c. I'm just sayin' . . . See Angel Arts and Gifts for a discussion of these issues that seems to be somewhat well-researched.)

Finally (what, so soon?), I had two minor goals on this trip.

- First, while crawling the Web and deciding where I would go - after all, virtually every city in the world has one or more cemeteries - I encountered several photos of sculptures that seemed particularly beautiful or touching, but had no information about whose grave they represented and in some cases not even an indication of which cemetery they might be found in. For example, one particularly sentimental little cherub (see Friedländer below) was simply credited as being in "Zentralfriedhof Wien", and another weeping child (see Familie Dasatiel in Hietzinger Friedhof below) even less specifically, "A Cemetery in Vienna". Well, Vienna has something like fifteen significant cemeteries. Big help! So, I made a list of ten or fifteen sculptures I wanted to fully document and identify. (I'm proud, and relieved, to report that I was 100% successful in this effort.) In general, my standard is to record and provide as much "credit" as possible, including the name of the defunto/a (deceased) and the name of the sculptor, and possibly other artists, who created their monument.

- Second, I wanted (of course) to explore, or in some cases, re-explore, the cities in which the cemeteries were located, so I did a bit of that, too, and have included a few "tourist snapshots" below. (No selfies, I assure you.)

We're off.

Cimitero Monumentale di Torino - 23 September 2016

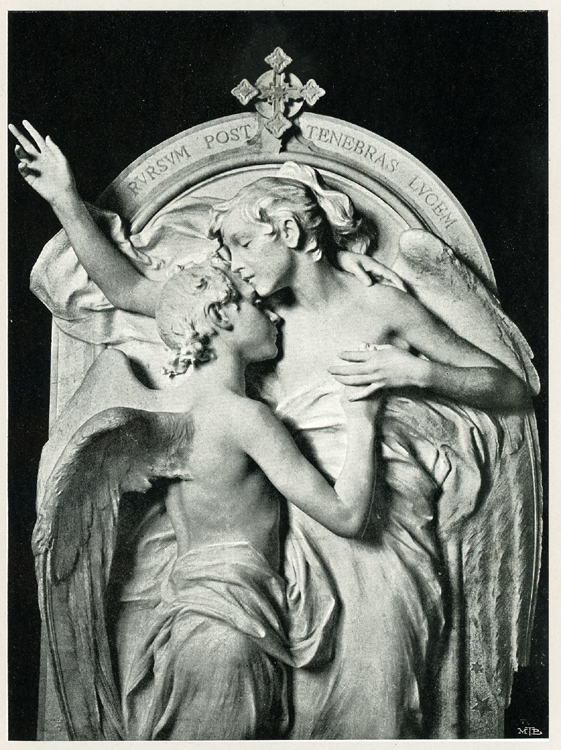

The first city I visited was Torino, and the first monument I wanted to see was this remarkable bas-relief, sculpted by Lorenzo Vergnano (1850-1910) to the memory of Giuseppe Pongilione (1823-1900). It is a clear example of one of my themes of interest, the Guiding Angel, who points the way to heaven for the (presumably) appreciative Signore Pongilione. The Angel had to wait awhile, though, as this impressive sculpture was commissioned by Pongilione and completed in 1886 - 14 years before his death!

[THEME: Guiding Angel]

Encountering the Pongilione monument in person carried an added bonus, as it contributed greatly to my understanding of another of my themes: restoration of funerary monuments. At the moment I arrived, a team of restoration experts from the local University were just finishing their cleanup work, and the leader of the team, a professor of Art History (whose name I regrettably did not record) was kind enough to spend considerable time discussing the process with me.

[THEME: restoration]

The monument stands at the corner of a portico, a covered walkway open to a central courtyard, which is quite common in XIXth century Italian cemeteries. Unfortunately, the building was bombed during WW II in the vicinity of this sculpture, and the damage went unrepaired until the 1980s. As a result, rain water leaked through the roof causing considerable problems. The face of the cherub holding a cloth in the center foreground is completely gone. Most of the rest of the work, however, was merely (!) stained and mildewed, and could be cleaned.

The tomb of Giovanni Battista Marchino (1767-1843), sculpted by Stefano Butti (1807-1880), is another example of the theme of the Guiding Angel.

[THEME: Guiding Angel]

This astounding building is visible from most points in the city. I thought it might be a government building or enormous church. It is the Museo Nazionale del Cinema.

In the XIXth century, a strategic tunnel was constructed connecting Italy and France by rail. This monument, using boulders removed during the excavation, stands in the Piazza Statuto to commemorate the triumph of reason and hard work over the forces of nature. It also commemorates the workers who died during the project, and there is a fair amount of dark imagery, even talk of Satanic influences, in this monument, as there is in Torino in general. (It is said by some that the gates of Hell are in Torino's sewer system.)

Cimitero Monumentale di Milano - 26-27 September 2016

The Cimitero Monumentale di Milano, like most cemeteries everywhere, has relatively "common" areas like this, especially in the newer additions.

I noticed in the Milano cemetery that a surprising number of graves had statues of San Giovanni/St John the Baptist as their monument of choice. (Other cemeteries might have many sculptures of Jesus, or just a cross above the grave.) This is the tomb of Pietro Pluderi (1874-1950). The key that identifies images of San Giovanni is the long, slender cross he holds. Note also the two-finger hand gesture, as I will return to this significant religious "code" later.

The next few photographs show more (but not all, by any means) of the San Giovanni sculptures here in Milano.

Tomb of the Viterbi-Grassetti family.

Throughout art history, San Giovanni Battista/St John the Baptist/Saint-Jean-Baptiste is portrayed as an adolescent or very young man. Here on the Tomb of the Bonfati di Belforte family he is shown in maturity, still holding the characteristic tall, thin cross. Apparently, the patriarch of this family, listed first in the inscriptions at the foot of the sculpture, was named Giovanni Battista, and died in 1914.

This sculpture on the Rossi family tomb is different from most, as it portrays San Giovanni and Jesus together.

Another variation finds San Giovanni seated at the tomb of Cesare Maritano (1843-1885). This time he is accompanied by a lamb, another typical feature of images of this saint.

The colossal tomb of Antonio Bernocchi (1859-1930) rises above all the other monuments in what one Web site describes as the style (if not the height) of Trajan's column in Rome. The inscription around the base is Latin, and the style is a combination of Art Deco (structure) and Realism (sculptures). An inscription inside the monument designates Bernocchi as Senatore del Regno - Senator of the Kingdom. The Senate of the Kingdom was abolished in 1947.

The Sesana family tomb is unusual for what we see, and for what we don't see - i.e., what has been lost. Around the tomb itself are bas-reliefs of children and adolescents, who I assume are family members at various stages of their lives. You can see in the next photos that these bas-reliefs continue around the entire base of the monument.

What you can also see from these vintage images - the left is a postcard photograph, right is a picture of a model for the monument - is a large structure incorporating cross motifs and inscriptions into an impressive circular crown are no longer there.

Perhaps the most striking Art Deco monument here in Milano cemetery is this mausoleum for Arturo Toscanini (1867-1957) and his family. Part of its charm, of course, is the fact that it seems to be kept relatively clean.

In every cemetery, there is weirdness, or at least apparent weirdness. Some can be explained, some is shrouded in mystery. Frankly, I don't know what to make of this Symbolic sculpture on the tomb of the Manzi-Codecasa family. Perhaps the man is walking through the curtained gate into eternity, but why is the fully-clothed woman lifting her skirt?

This sculpture is remarkably similar

to one in the Kerepesi cemetery in Budapest

in memory of the

Kilian family.

In that one, however, the woman is an angel, and is not lifting her skirt.

[THEME: weirdness]

These are the Russo twins, born in 1925. Gerardo died in 1948, Antonio a year later.

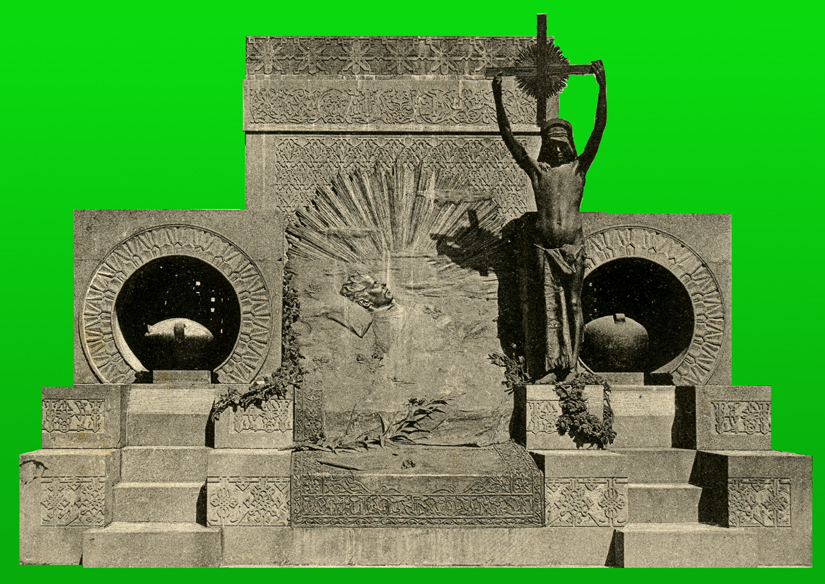

This, for me, was the most important monument to find. It is the tomb of Roberto Castelli (1875-1899) whose image lies in repose at the center of the sunburst. The sculpture, unlike most monuments, actually has a title - Christianity - and was completed in 1904 by Enrico Astorri (1859-1921), whose work can be found in several Italian cemeteries. Several art critics found on the Web describe the overall style as Middle Eastern, and one even speculates that the acolyte holding the cross may be a representation of St John the Baptist. The cross bears the Latin inscription, QUI SEQUITUR ME NON AMBULAT IN TENEBRIS [Who follows me walks not in shadows]. The sunburst around Castelli's likeness and on the cross itself further symbolize this idea.

Many cemetery monuments are artistically significant enough to have appeared on postcards using photographs made when they were relatively new. Through these, we can see what time has done, as well as the original detail and skill of the artist who created them. I've removed all the background clutter from this postcard image, so you can see the monument in its original conception.

This tomb for the family of Franco Dompé di Mondarco is more than it seems at first glance. It was built in 1957-1963 by Nando Conti (1906-1960), and inside is a Roman sarcophagus (burial vessel) from the II century CE. Also, take a look at the left rear of the structure in this picture, then continue down to my next photograph(s).

SCROLL TO THE RIGHT to see the entire image.

Around the sides and back of this mausoleum are these reliefs, about a foot high, of singers, dancers, and musicians playing instruments.

The tomb of Luigi Brusotti (1848-1905) looks to me to be Art Deco in style, but if it was built close to Brusotti's death, that would be too early, as Deco was introduced to the world in 1925.

Outside the cemetery, in the pleasant neighborhood of Porta Romana, we find this graffito at a crosswalk in the street. No, I don't have any idea what it means. (By the way: see the shadow? That's as close as I'll ever get to a selfie.)

Cimitero Monumentale di Verona - 28 September 2016

Verona's cemetery is relatively small, and straightforward.

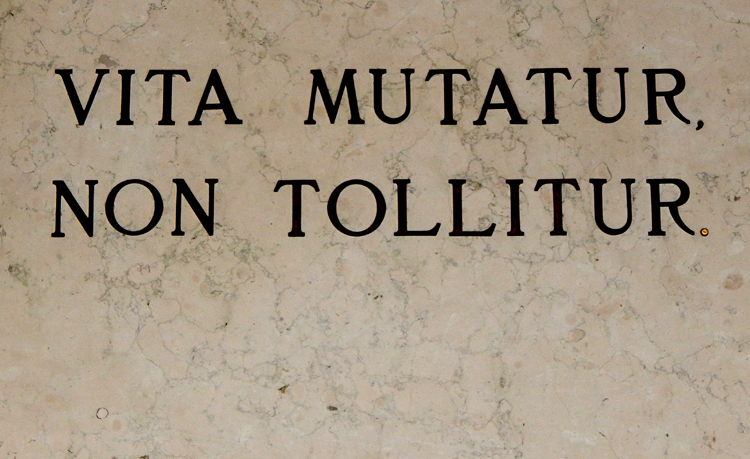

This is one of those captions that is somewhat at odds with other captions you see in cemeteries, and with various beliefs humans have about what happens when you die. The intended meaning probably is, "Life is changed, not taken away." It is interesting, however, that the meanings "take away", "remove", "abolish", "destroy" and so forth are not the primary meaning of the verb Tollo, Tollere. The primary meaning is more like "lift up", "raise" or "elevate". The first verb Muto, Mutare, moreover, also has multiple meanings, including "change" and "modify", but also "remove" and "spoil". This is an ambiguous slogan at best, which, if it were not in a cemetery, could be read as "Life is removed, it is not removed."

I don't feel comfortable poking fun at people's family characteristics, especially when they're dead (and helpless to respond). But funny is funny! and it's a legitimate cultural difference that makes it so, not something built into these people's circumstances or life choices. (Advance notice: if you agree that this one's humorous, there's one coming up in Vienna that's a riot!) Again, I mean no disrespect to this family, and I realise this is probably not in the least humourous in Italy.

How about a little music to calm things down!

As you'll see again below, I find the relatively rare bronze relief memorials (as distinguished from the bronze sculptures, which are not so rare) quite interesting. This detailed monument combines marble and bronze to depict the schools founded by Don Nicola Mazza, first for girls (on the left), and then a few years later for boys (right) who were neglected or too poor to go to school. It is the tomb of Francesco and Giulia Paletta Sigismondi, a noble Veronese family that apparently were generous supporters of the Istituto founded by Don Nicola Mazza.

This monument to Tiziano Fraccaroli is nothing short of breathtaking. The meaning of the sculpture is unclear (to me). The angels and people seem to be preparing to welcome the woman lying on the bier in front of them - the faint inscription is from the Latin Requiem - IN PARADISUM DEDUCANT TE ANGELI [May the angels escort you into paradise] - though the picture in the circle on the front of the bier is a man, around which is the name TIZIANO FRACCAROLI along with the date MCMXLI, and the floor-plaque in front of the bier also has the name TIZIANO FRACCAROLI on it, as if that's an actual grave. Nonetheless, it's stunning. It's one of those (many) funerary sculptures the spirit and essence of which cannot be captured in a photograph. Being in its presence is a completely different and special experience.

Perpetual mourners at Verona.

Cimitero Monumentale di Staglieno, Genova - 30 September 2016

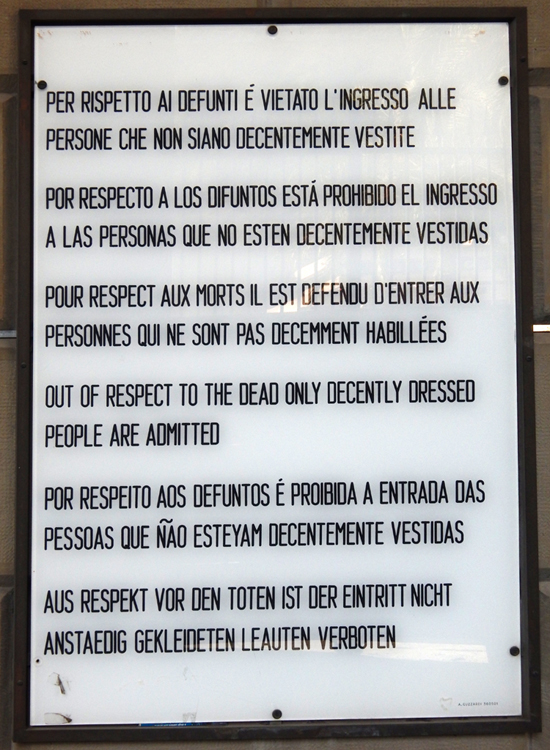

Of all the cemeteries visited on this trip, Staglieno is the only one that I had seen before. This notice is at the main ceremonial entrance on the South side, which isn't always open. The entrance used by most visitors is on the West side, which doesn't have this sign as far as I could tell. (Still, no-one was ever inappropriately dressed while I was there, except for a few statues, maybe.)

As I've explained elsewhere, my first visit to Staglieno was to see the haunting, magnificent Angelo Nocchiero [Angel-Helmsman] of Giovanni Scanzi (1840-1915) which he placed on the tomb of Giacomo Carpaneto (1811-1878) in 1886. The cemetery itself used the Nocchiero for the cover photograph on their 2014 brochure. The Web is full of images of the sculpture, including one in my own vacation pics from 2014 on this Web page, or you can enter "Staglieno" and "Carpaneto" into a Web browser and take your choice.

The Nocchiero is perhaps the most vivid example of my favourite

sculptural theme, the Guiding Angel.

When I posted my own photo of the sculpture in my vacation pictures from

2014, I commented that, like most art work at Staglieno, the

Nocchiero was covered with "dust and grime", and that

"one can only imagine just how stunning these marble sculptures were

when new."

On this visit, I see perhaps a miracle in the making: the Nocchiero

is shrouded in plastic and scaffolding as a restoration is nearing

completion.

I presume new, sparkling pictures of this masterpiece will be appearing

on Web sites any day now.

[THEMES: Guiding Angel; Scanzi model look-alikes; restoration]

Staglieno has a number of sculptures executed by Maestro Giovanni Scanzi besides the masterpiece noted just above. I knew this on my first trip (2014), but on this occasion began to notice that in several of his works, the young male angels resembled each other. Compare for yourself the above-mentioned Nocchiero (1886, viewable in my 2014 vacation pictures and at any number of other Web sites) with this Scanzi sculpture from 1877 (tomb of Carlo di Giovanni Battista Casella [1818-1874]) and the next few monuments pictured below.

[THEME: Scanzi model look-alikes]

This vintage photograph from the early XXth century, or possibly earlier, allows a comparison with the statue's current condition, hopefully demonstrating what might be accomplished with a little artistic restoration.

[THEMES: Scanzi model look-alikes; restoration]

This 1915 sculpture is on the tomb of Bertollo Ferralasco (sometimes noted as Nicolo Bertollo).

[THEME: Scanzi model look-alikes]

(Photo "borrowed" from Wikipedia, credit: Twice25 & Rinina25)

This bas-relief by Scanzi is on the tomb of Elisa Falcone (1893), in the Porticato Inferiore Levante

(image of the artist's plaster model from Ferdinando Resasco. Staglieno Camposanto.

Milano: Stabilimenti Menotti Bassani & C., 1904)

[THEME: Scanzi model look-alikes]

And finally for the Scanzi comparisons, consider this sculpture on the tomb of the Giacomo Pastorino family (1896). To my eyes, a case can be made for the same model being used for the male angel in each piece.

[THEME: Scanzi model look-alikes]

Here is one of Staglieno's restoration success stories. This monument to the wife and daughter of James Fletcher, who was appointed the American Consul at Genova in 1883, was fashioned by Luigi Brizzolara (1868-1937) in 1896, and placed in the American Sector of Staglieno, an outdoor area of the Camposanto. Being outdoors, it was particularly vulnerable to mildew and other biological growth that was corroding the surface.

[THEME: restoration]

(The sculpture's transformation can be seen here.)

In 2015, a remarkable organisation known as the American Friends of

Italian Monumental Sculpture (AFIMS) unveiled their restoration of the

Fletcher Memorial, as seen here in my humble photograph.

Kudos to this group, which is located in the United States of America,

and concentrates its restoration efforts on Staglieno.

(Yes, of course, they gladly accept donations.)

[THEME: restoration]

Now we deal with another of my themes, indeed one of my "pet peeves": lack of credit or documentation for cemetery sculptures when posted on the Web. One of the less-attractive practices on the Web is the re-posting of pictures (the Twitter equivalent is re-Tweeting) which often gives the impression that the re-posted picture was created by the re-poster herself or himself. When this is done, it is usually the case that no identifying information follows the picture, and those of us who find such a post in Web searches can neither find the original source nor search for other similar pictures. In scholarly circles, this is known as plagiarism.

As I noted at the top of this page, one of my minor goals was to identify

and document a number of images more fully.

This is the first one.

This haunting face is seen often on Pinterest and elsewhere.

It is one of two angels sitting at the corners of the tomb of Bernardo

Figari (died 1880, age 37), a monument sculpted by Giacomo Moreno

(c.1832-1910).

One arrogant Web site where his face was posted labeled him as

"angelo sporco" ("dirty angel"). How rude - even though

true!

[THEME: missing credit for deceased and/or artist on Web posts]

Here is another Staglieno statue that is usually posted without proper credit. Once I found it, I was impressed at the angel's monumental size, as compared with the life-size person at the base. The sculptor Filippo Silvestro Giulianotti (1851-1903) created this in 1889 for the tomb of Cesare Corallo (1824-1884). It's on the hill in the Boschetto Irregolare, to the West of the famous mausoleum of Giuseppe Mazzini.

[THEME: missing credit for deceased and/or artist on Web posts]

The tomb of Giovanni Battista Dentone, sculpted in 1883 by Giuseppe Benetti (1825-1914) uses a mixture of materials, including a bronze diorama of an event in the life of Christ. He appears to me to be defending an accused woman, perhaps Mary Magdalene.

When I first saw this monument back in 2014, I thought it was an interesting twist to have a sculpted angel actually writing something on the grave marker. As it turns out, this is not unique, as I found several other examples (see below) in my visits on this journey. This is the tomb of Francesco Bartolomeo Savi (1820-1865) created by Augusto Rivalta (1837-1925). The angel is writing the number "1865", which is the year of Savi's death and the year the monument was erected.

[THEME: angel/person writing on monument]

The great Cappella Raggio (1896, architect Luigi Rovelli [1850-1911]) is what you might call a "fan favourite" at Staglieno, for obvious reasons. Its style is modeled on the great Duomo (Cathedral) of Milano. On my previous visit in 2014, as my pictures then show, it was surrounded by Italian cypress trees so that from a distance, only the spires could be seen. Up close, the gate to the surrounding grounds had a lock with decades of rust betraying its lack of use.

This time around was a different story. The gate had a new, clean lock on it and the trees in front had been removed, so that a picture of the whole structure is now possible, revealing a colourful mosaic above the entry door.

The Cappella Ottone (1898) designed by architect Marco Aurelio Crotta (1861-1909) is unusual, or was at least on this trip, in that the door was open and you could walk inside.

Inside it was in serious disrepair, but another unusual feature revealed itself: the memorial to its "occupants" Giorgio and Giuseppina was on the ceiling!

The monument to Italino Iacomelli (1925) is first a heartbreaker (one of the Themes mentioned at the top of this page), but is also an example of striking, even terrifying Realism. Five-year-old Italino was an orphan, murdered while playing with a hoop in public gardens in Genova. It's all in the sculpture, children.

Some of the "monuments" in cemeteries like Staglieno are miniatures, merely niches holding ashes or "shelves" (if you'll excuse the expression) of coffin-sized spaces stacked five or six high in interior porticati. This monument to Rocco Macchiavello (1841-1900), signed in the lower right by sculptor E[ttore]. Sclavi, could be another example of the Guiding Angel, this time mourning his patron as would a friend.

[THEME: Guiding Angel]

Back out on the streets of Genova, we make another visit to the magnificent Basilica della Santissima Annunziata del Vastato. This burial stone is in the floor of the main church, and appears to have been placed here in 1527.

Add this to my collection of "weird sculptures of the world" (along with the Fallen Police sculpture in Padova that I posted in my 2014 vacation pictures). If it has any meaning beyond bizarre, I don't have a clue what it is. You can see it for yourself in the courtyard of the Palazzo Reale in the Via Balbi, which is now a museum.

[THEME: weirdness]

OK, so here's another weirdness, this time in Genova's Porto Antico. Presumably that's Neptune, standing on the head of a much smaller man (or boy) on the ship's prow. I guess they ran out of topless mermaids.

[THEME: weirdness]

UPDATE (2017-07-11): I've just run across some information about this ship, and its weird front end. According to www.atlasobscura.com/places/roman-polanski-s-neptune the galleon is a prop from Roman Polanski's 1986 film Pirates. Apparently, though it was made for filming and could have been just a fancy shell, it is a fully-functioning galleon with a diesel-powered motor. More recently, of course, this would simply be rendered by computer-generated imagery (CGI), with no need to take up space in the Port of Genoa.

Cimitero Monumentale della Certosa di Bologna - 3-4 October 2016

Cimitero Monumentale della Certosa di Bologna was founded on the site of a former monastery, dissolved by Napoleon just in time for repurposing it as a burial site for the city's dead. Monastery buildings were incorporated into the cemetery, and many of the monks' burials and inscriptions from the XV century onwards are still visible. The new cemetery became famous for its works of art, and was visited by the likes of Charles Dickens, Lord Byron and others. Among those entombed here are the castrato Farinelli (1705-1782), composer Ottorino Respighi (1879-1936) and automobile magnates Alfieri Maserati (1887-1932) and Ferrucio Lamborghini (1916-1993).

The Bologna Certosa is different from many other Monumental cemeteries in that many of the burial porticati are entirely enclosed, not open to central courtyards or otherwise exposed. Skylights provide a soft, pinkish glow to many of the Columbaria and walkways creating an unique, surreal, and ultimately peaceful atmosphere. It also seems to have more inscriptions in Latin than most of the other Italian cemeteries I visited.

In this monument, Fabio Frassetto (1876-1953) has a conversation with his son, Flavio, who was killed in WW II. The skull between them symbolizes the nature of their discussion. In this first of three pictures, borrowed from Wikimedia and dated 2008, we see Padre Frassetto emphasizing a point with his outstretched hand, all fingers intact, as originally intended by sculptor Farpi Vignoli (1907-1997).

In this photograph, also from a Web posting and dated 2010, his gesture depends on only three fingers.

Now, in my photograph taken in 2016, he's down to two. Such are the vicissitudes of outdoor sculptures in free-access areas, despite social conventions that tend to respect the departed and their resting places. (Oh, God, I just had a horrible thought. What if the index finger goes next?)

In cemeteries with tens, even hundreds of thousands of graves, niches, mausolea and other resting places, originality can be greatly appreciated. Even the great Monumental cemeteries where rich patrons hire the finest artists to create their memorials, they tend to fall into categories - angels, weeping family members, bewildered children, religious figures, and so forth - and ultimately become somewhat predictable. Sculptures like this one, therefore, are what true art-lovers appreciate.

[ADDED 2018-09-09: I've just realised that I failed to do something that I've criticised others on the Web for failing to do, so I'll make it up immediately: this 1952 monument by Farpi Vignoli (1907-1997) is on the tomb of Ennio Gnudi (1893-1949). Sorry for the delayed information.]

This courtyard surrounded by a colonnade is Chiostro VII, containing many fine monuments. In the center of this picture is the Montanari family tomb.

The Montanari tomb is unusual, in that an angel reclines in front of it, obscuring the family name.

In my pre-travel research, I found photographs of this tragically disfigured monument, as well as vintage photos of what it once looked like (see below). As it was not identified as to the deceased nor the creative artist, it was one of my priorities to find it and identify it. (Actually, I'd like to find the vandals who disfigured it and disfigure them in similar ways, but that's just the John Wayne in me coming out.)

[THEMES: missing credit for deceased and/or artist on Web posts; restoration]

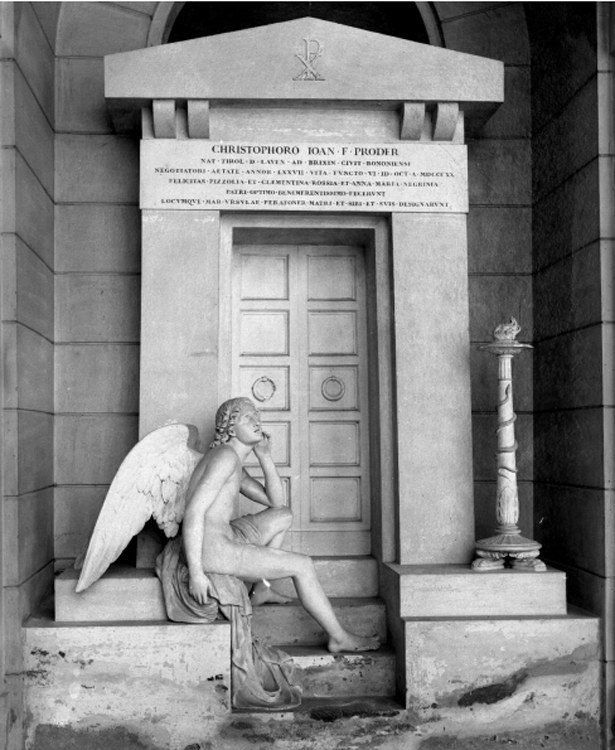

This is (or, rather, was as it once looked) the tomb of Christoforo Ioan Proder (who, according to the inscription, died in 1820, age 77), created by sculptor Cesare Gibelli (1806-1885). This could have been one of Gibelli's first works, as he was barely fourteen years old when Proder died.

The Proder monument (see above) may be difficult to restore, as it would require actual and extensive reconstruction. This kind of monument, however, could be restored by cleaning methods if interested benefactors could be found. Alessandro Massarenti (1846-1923) created this sculpture for the Monument for Mario Cornacchia and Family (1890).

Vintage photos, taken near the time of the creation of these sculptures, once again show us what once was, and what could be again.

[THEME: restoration]

Here you can see the warmth and solitude of the Sala del Columbario at Bologna Certosa. The ambience is due in part to the pale yellow paint on the walls and the indirect lighting coming from the windows and skylights. The monument in the center at the crossing is interesting in several ways.

Originally the sculpture was to commemorate Napoleon's sister, Elisa Bonaparte (1777-1820). The great sculptor Lorenzo Barotlino (1770-1850) was commissioned to sculpt a likeness of Sig'ra Bonaparte, but the block of marble he chose had a flaw - a black vein running right through the face of the deceased. The family refused to buy a new block of marble, and Bartolino also refused to provide a new marble block himself. Later the sculpture was sold to the Marquis Malvezzi Massimiliano Angelelli, who put it here on his family tomb (constructed between 1833 and 1854).

In its new location, the sculpture was referred to as Pallas and the Genius of Glory. This is how it looked in its early days.

[THEME: restoration]

Bruto. Despite the way his parents dressed him, at least they named him for success. His early loss, barely three years old when he died in 1874, was obviously devastating to his parents Giovanni and Luigia Ricci di Cesena.

[THEME: heartbreaker]

This sculpture is a memorial created by sculptor Paolo Aleotti (1813-1881) to be placed on his own final resting place in 1881. Another heartbreaker, it is widely copied on sentimental Web sites, and rarely credited as to the deceased or the artist (in this case, one and the same).

[THEMES: heartbreaker; missing credit for deceased and/or artist on Web posts]

Angelo Minghetti (1822-1885) was a ceramic artist, so decorating his tomb with ceramic art (by Alessandro Massarenti [1846-1923]) is obviously a fitting tribute.

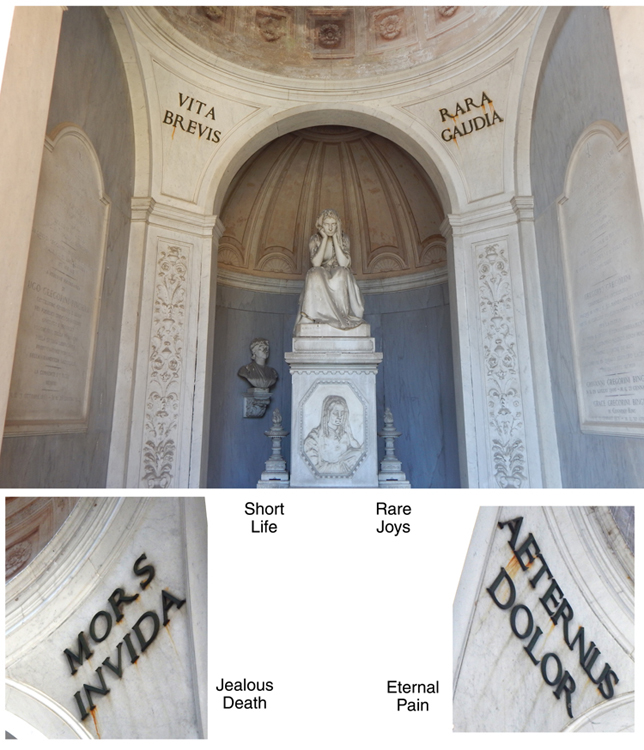

The Cappella of the Gregory Bingham family is an area within one of the general enclosed porticati. Between each of the four arches that define the space there is a slogan, reproduced (with my own translations) here. This is a rather dark view of life, death and the hereafter. The central sculpture of the chapel is no day at the beach, either. La Desolazione [The Desolation], by Vincenzo Vela (1820-1891), was placed here in 1875 to great acclaim within the art community.

[THEME: slogans]

I don't think this portrait, on the tomb of Antonio Martinetti (died 1885, age 70), needs any comment, but if I had that one full of lira . . . never mind.

Bruno Beliossi's space in Bologna Certosa is no more than a cubbyhole, presumably housing his ashes. The top picture shows the tiny niche, with the name-gate closed.

On closer inspection, it turned out that - unlike the vast majority of

small niches and large mausolea alike - there was no lock on the gate.

I certainly wouldn't have disturbed anything inside, and didn't, but by

opening the gate, I

was able to see the contents more clearly and to determine that the little

bottle with the white top next to the fading photograph actually had some

liquid in it.

I wouldn't begin to speculate what it might be. I just closed the gate

and went on my way.

[THEME: weirdness]

Here is another of the bronze reliefs that I find so interesting, mostly because the vast majority of sculptures, reliefs and otherwise, are marble or plaster. The inscription being held by the scugnizzo with the wings on his helmet identifies this as the resting place of Dionisio Antonio Calzoni (died 1900) and his Widow (died 1925). To my semi-trained eyes, the style of this sculpture is Art Deco. The widow's death in 1925, the beginning of the Deco period, would tend to confirm this.

By far the most moving, and possibly the most complex monument in the Bologna Certosa is the Ossuario ai caduti partigiani [Boneyard for the Fallen Partisans], dedicated on 31 October 1959. The partisans, in this case, were Italians who resisted the German occupation during World War II, and died in that cause. Piero Bottoni (1903-1973) was the architect and the sculptors were Genni Wiegmann Mucci (1895-1969) and Stella Korczynska (died 1956). One enters the monument by way of two staircases to the underground vault. The structure above is cone-shaped - eerily similar to the nuclear reactor cones that rose later around the world - and open to the sky.

The ashes of five hundred of those partisans are interred here, in niches around the wall. Victims of the death camp at Gusen were subsequently interred here as well in 1961. In the centre are several bronze figures straining upward, as if rising from the ground.

This resurrection motif is continued with the bronze figures ascending the internal walls of the inverted cone, moving toward the light.

Ultimately, the figures stand triumphantly on the rim of the cone, in full sunlight and freedom from both death and oppression.

The colossal monument can be seen from many parts of the Certosa, a dominating presence and reminder of oppression and ultimate victory. The inscription in Italian, repeated several times around the outside rim of the structure, sums it up: Liberi salgono nel cielo della gloria - The free ascend into the sky [heaven] of glory.

Cimitero delle Porte Sante, Firenze - 5 October 2016

The Cimitero delle Porte Sante in Firenze is actually a graveyard originally for a mediæval monastery which is now the Basilica di San Miniato al Monte.

One of the notable sculptures at Porte Sante is this graceful angel which, like so many others, is seen often on the Web without any information as to creator nor dedicatee. The master Augusto Rivalta (1837-1925) sculpted this figure for the tomb of Pellas de Maillane in 1890.

[THEME: missing credit for deceased and/or artist on Web posts]

The tomb of Pasquale Romanelli (1812-1887) is interesting for several reasons. Romanelli, a disciple of Lorenzo Bartolini, was a well-known sculptor and this memorial to Pasquale was made by his son Raffaelo (1856-1928), also a successful sculptor.

The Romanelli monument originally held a bust of the deceased on the central pedestal, as seen in this photo, but missing in my photo just above. (This photo from the University of Maryland Baltimore County digital collections, and is dated 1998/2000.)

Ice cream available in the pharmacy? I wonder what's in it.

Hundreds of buildings in Italy have sculptures above or at the sides of entrances, like these on either side of the main entrance to the Biblioteca Nazionale. What's interesting to me is that the two giants on the left are modestly covered, while those on the right are no sheets to the wind - and one is looking at the other, as if wondering what happened to his toga . . . or something.

Putti (these on the back side of the Biblioteca Nazionale) are often not modestly covered - why bother!?. The shields they hold bear the inscriptions RIME and EGLOGHE, presumably referring to Rhyme and Eclogue forms of poetry.

Hey Dave! Don't stand up on the bus! (This scene seen at the spectacular tourist view-point called Piazzale Michelangelo.)

A contemporary take, perhaps, on the classic (and racist?) lawn jockey, this elongated waiter stands outside the Rubaconte Pizzeria in the Lungarno delle Grazie, a street along the North bank of the Arno.

Cimitero del Verano [Campo Verano], Roma - 7-10 October 2016

According to the inscription in the style of many Roman buildings, this central building at Roma's Campo Verano cemetery was built during the papacy of Pius IX in the fourteenth year of his sacred office. In other words, 1859.

One of the first things I noticed on entering the Campo Verano was the difference in size of portraits of the deceased on the graves. Aside from the portraits sculpted in marble or bronze, when pictures of the deceased are seen in other Italian cemeteries, they tend to be relatively small enameled photographs, usually somewhere between six and ten inches across. Here it is common to see these much larger pictures, which, I learned later, are enamel painted on lava stone using a technique perfected by Filippo Severati (1819-1892) for which Pope Pius IX bestowed on him the title "porcellanista". This is the family tomb of Giuseppe Cecchini (1865-1929), just inside the main entrance to Campo Verano.

The side and back of the Cecchini tomb shows portraits of more family members.

At the tomb of Camillo Ciacci (1838-1908) and family, the sculptor (unknown to me) uses Realism to show a boy perhaps trying to decide how he can console his grieving sister.

This rendering of the famous she-wolf and twins of the founding of Rome stands atop the grave marker for Goffredo Mameli (1827-1849), author of the lyrics of the Italian National Anthem and an important figure in the Risorgimento (reunification) of the XIXth century. Below this large marker lies a marble sculpture of Mameli himself, by the artist Luciano Campisi (1860-1933). The monument was erected in 1891. Here's my question: What the heck is Remus reaching for there with his left hand? (Or is it Romulus?) The food, my boy, is in the middle.

Compare this picture that I took a few days later at the Musei Capitolini of the original (or at least the oldest known) version of this ubiquitous symbol of the city. No unseemly groping here. Strictly business! (By the way, recent scientific and artistic analysis points to a mediæval origin for the wolf - though some still believe the original tradition that it dates to the V century BCE. The twins were added in the XV century when Pope Sixtus IV donated it to the Capitoline.)

This statue was one of those I wanted to identify after finding its uncredited picture on several Web sites. The presence of the ancient Roman vexillum seemed unusual. Finding the statue was not easy, a common problem in such large burial grounds. Without knowing the name(s) of the deceased, even the officials in the cemetery offices (if you can find them) can't help, which is understandable when there are tens of thousands of monuments of this size spread over 80 hectares (nearly 200 acres).

In a stroke of genius on my part (or was it luck?), I showed the picture I had brought along to a cemetery worker I encountered, and while he wasn't sure, he did recognise the statue and pointed in the direction where he thought it might be. He was right.

In an area covering a small hill, this angel stands alone at the

crossing of two paths.

It is a memorial to the crew of the gunboat Volturno, lost in

the attack of 1896 at Lafolé in Somalia.

(I am not able to identify the sculptor.)

[THEME: missing credit for deceased and/or artist on Web posts]

Dionisio Romeo Chiodi died in 1956 at age 12, and his family and community (rightly) decided to memorialise him as a hero. As the plaque on the right explains, one day he and three friends, including his younger brother, decided to go swimming in a pond. Suddenly, Dionisio realised that the other boys were about to drown, so he rescued his brother and one other boy, then, despite being fatigued, went back to rescue the third where they both disappeared under the water. (Sculptor could not be determined.)

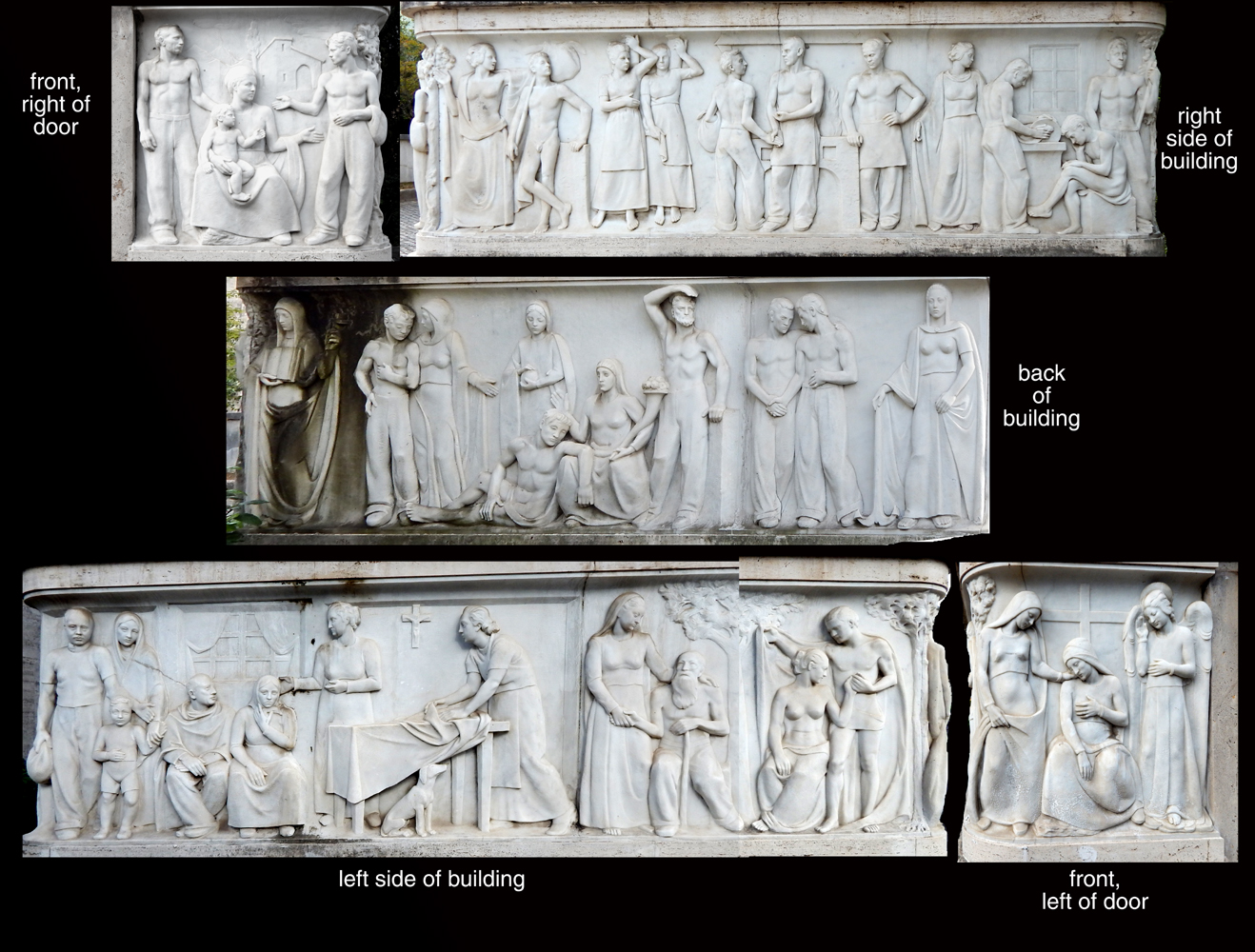

So many mysteries are found in great cemeteries. This monument to Matteo Torriani has a most interesting series of detailed bas-reliefs around the entire structure (except for the doorway), with no indication of the artist that I could find. The date of the monument was also elusive, though the Art Deco look of it suggests it may be sometime around the late 1920s. (That's me, once again trying to sound like an art expert!)

SCROLL RIGHT (or enlarge browser) TO SEE ENTIRE IMAGE

The reliefs around the Torriani monument seem to tell a story, but one that I can not decipher. I've presented the panels in order here, so if there is a sequence, perhaps they make sense from top to bottom (which would be from right of the front door around to the left), or from bottom to top (the reverse). The best I can come up with is that they might portray the journey of the Biblical Prodigal Son, but there are a lot of "scenes" that aren't part of the original story.

This was the sculpture mystery at Campo Verano that I most wanted to solve, namely, what did the monument symbolize and who created it. I was armed only with pictures like this, depicting an apparently dead youth, another youngster huddled over him, and the astonished angel above. My arrival at the monument itself, and then the waves of realisation as to just what this all represented, was nothing short of a mystical experience for me. (Unfortunately, I have not yet determined the name of the sculptor[s]/creator[s] of this monument.)

[THEME: missing credit for deceased and/or artist on Web posts; heartbreaker]

After walking around Campo Verano for at least six hours, trying (but surely not succeeding) to investigate every trail and walkway in search of this sculpture, I was not only getting tired, but getting discouraged that this massive Camposanto was going to keep its secret as to who was memorialised by this deeply moving work of art.

As I circled back around toward the central porticati of the cemetery, I finally decided I should give it up and, perhaps, return the next day. Walking along, I looked down each pathway until I saw an entrance into the main structure at the cemetery's centre, and I turned down that path intending to give up the search and go back to the hotel. The very first monument on my right was the one I had been looking for those many hours. I am not one to believe easily in divine intervention, but this discovery could not have been by chance. I felt I was meant to find this monument, and may even have been guided to it.

The tomb is a mausoleum for the Lombardi family, built following the tragic deaths of these two boys, Maurizio (age 14) and Daniele (almost 10), seen here at the right of the monument in happier times, and at the left (see photos above) apparently in death. The angel is right to be shocked, horrified. The boys both died on the same day, 5th October 1943 in an enemy raid at Bologna. That enemy, I deeply regret to say, was the 12th USAAF (United States Army Air Force), which took out the marshaling yard at Bologna, and also happened to bomb the city itself, killing 80 civilians. (Source: Claudia Baldoli and Brendan Fleming, Editors. A British Fascist in the Second World War. London: Bloomsbury, 2014, p.215, note 269) The identical inscriptions on each burial niche express the final heartbreak: "La furia nemica spezzò la tua tenera vita ma non la tua anima pura" ["The enemy's fury broke your early life but not your pure soul."] Requiescant In Pace

The relatively short walk from my hotel to the Campo Verano cemetery took me along the Via Tiburtina and past the Porta San Lorenzo, one of many examples of ancient Roman walls and gates still standing around the city.

While looking for the elusive (at least for me) Chiesa di San Pietro in Montorio on the Janiculum Hill, I came across this tribute to one of Rome's younger heroes, the fabled Righetto.

Many cultures have child martyrs of wartime. In France, it's the drummer-boy Joseph Bara (1779-1793), who was killed during the Revolution because he refused to give the enemy the two horses he was leading; and in México, the six Niños Héroes of 1847, defending their military academy and their flag at Chapultepec against invading forces of the United States of America. Righetto was a 12-year-old from Trastevere (just down the Janiculum Hill from where the statue stands today) who participated personally in the defense of the Republic under Garibaldi, and died in 1849 on the banks of the Tiber when a grenade exploded in his hands. His courage grew into a symbol of Roman resistance. This bronze, placed here in 2005, is a copy of L'Audace Righetto, sculpted in marble in 1851 by Giovanni Strazza (1818-1875). The original now stands (with his trusty dog) near the lobby staircase in the Palazzo Litta in Milano.

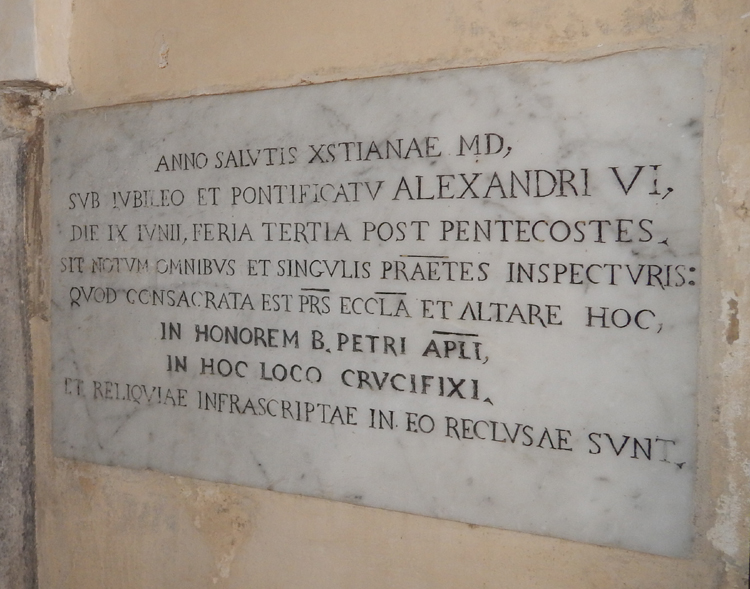

San Pietro in Montorio interested me because of the Tempietto (Little Temple) built beside it at the beginning of the XVI century. It is regarded by architects as a minor miracle, an almost-perfect building.

According to this inscription, the building dates to 1500 during the papacy of Alexander VI, and was built IN HONOREM B. PETRI APLI IN HOC LOCO CRUCIFIXI [In honour of Saint Peter the Apostle, Crucified in This Place].

The above plaque is on the side of a passageway leading to the lower level, which was not open to the public, but could be viewed through a metal gate.

In the 1930s, the City of Rome decided they needed a new Forum, so they built the Foro Italico and its centerpiece, the Stadio dei Marmi.

(You may need to SCROLL TO THE RIGHT, or enlarge your browser window, to see the entire picture here.)

Stadio dei Marmi is a remarkable sports stadium, with colossal statues of (presumably ancient) Roman athletes - yes, all male - representing different sporting activities around the entire perimeter.

As for the "original" Foro Romano, there is a convenient and spectacular view from the SouthEast side of the Musei Capitolini.

I didn't intend to re-visit Sant'Ignazio di Loyola, having been there in 2014, but I was in the neighborhood, so I stopped in.

The ceiling is nothing short of a miracle. (You may need to SCROLL TO THE RIGHT or enlarge your browser window to see it all.)

I photographed it in 2014 and posted the picture on this Web site, but decided to do so again, since I now had a much higher-definition camera.

Near Sant'Ignazio, and also near the Fontana di Trevi, is this little house, now a small shop for tourists. The inscription, probably original, says simply, Peace [Be] To This House.

A Brief Reflection on Cemetery Sculpture

The Ruhenden oder Trauernden Engel of Austria

Flattery/Imitation, or Plagiarism?

Here we have a question for the real art historians which I, as an armchair art lover, am not able to answer. In 1829, the widely-respected Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844) placed this bas-relief on the base of the memorial to Wlodzimierz Potocki (1789-1812) in the Wawel-katedralen (Royal Archcathedral Basilica of Saints Stanislaus and Wenceslaus on the Wawel Hill) in Krakow. The image has become iconic. The angel's downcast face to some suggests resting and reflection - the Ruhenden Engel - while others interpret grieving - the Trauernden Engel. The torch, probably representing the fire of life, is extinguished and upside-down, and he often holds a wreath in one hand, perhaps a reward for a successful life now ended. This is obviously Symbolic sculpture, with Classical features, and probably represents the departed soul's Guiding Angel, whose task is now finished.

[THEMES: Guiding Angel; iconic Grieving Angel]

Given the fact that this image is seen so often, with minor variations, in Monumental Cemeteries - mostly, as it turns out, in Vienna, or so it seemed on my travels - the question for the art historians is whether this relief by Thorvaldsen in 1829 was the original, or whether it was already a common concept among artists making funerary sculptures. It seems almost inconceivable that Thorvaldsen would have simply copied another artist's work. Also, while ready-made funerary sculptures have been available, especially in modern times, I would imagine that most of the examples presented here below are original works of art, each one showing at least minor variations in pose, draping of garments, size and position of wings, and so forth. Imitation in art is no crime, of course. The question, again, is whether Thorvaldsen was the first, or was the image already in the consciousness of the art world of his time?

Grabmal Vincenz Klamert (died 1938) und Familie, Zentralfriedhof Wien

the monument is signed "F. Wasitzki"

[THEMES: Guiding Angel; iconic Grieving Angel]

Zentralfriedhof Wien, in front of the Richter family monument

(this photo is borrowed from another Web source, so it is unclear if the angel is actually part of the Richter monument)

[THEMES: Guiding Angel; iconic Grieving Angel]

Zentralfriedhof Wien, unknown monument

[THEMES: Guiding Angel; iconic Grieving Angel]

Grabmal Auguste Winter (1858-1919), Zentralfriedhof Wien

[THEMES: Guiding Angel; iconic Grieving Angel]

Grabmal Hans Janda (1887-1950) und Familie, Zentralfriedhof Wien

[THEMES: Guiding Angel; iconic Grieving Angel]

Tomba Famiglia Weller (c.1883), sculpture by Salvino Salvini (1824-1899), Certosa di Bologna

This is a significant variation from the above; first of all, it's found

in Italy, not Austria; and the angel is decidedly younger than the

others; still, the pose and the downturned torch place it squarely in

the Ruhenden/Trauernden Engel tradition.

[THEMES: Guiding Angel; iconic Grieving Angel]

Here's where the fly in the ointment hits the fan (if I may mix the metaphors rather freely). The St Marxer Friedhof Wien is older than many of the other Viennese burial grounds. In fact, most of the burials there occurred well before the end of the XIXth century. This monument is on the grave of Josef Visser, whose inscription notes that he died in the 1790s (I was unable to read the final number). If this is the original monument, that means it was placed here several decades before Thorvaldsen sculpted his Potocki bas-relief (see above), and the elements are here: downturned torch, angel reflecting or grieving, holding his head in his hand. (Of course, as always, the sculpture could be a later addition to the grave site.)

[THEMES: Guiding Angel; iconic Grieving Angel]

Another variation at St Marxer Friedhof has this angel crouching lower than most, still with the downturned torch and wreath. This is the resting place of the Wolny Family (1844).

[THEMES: Guiding Angel; iconic Grieving Angel]

Yet another variation, on the grave of Infantry Cadet Franz Bobel (1843-1859), the angel is seen from the front, rather than the side. (This is one of those sculptures seen on the Web without attribution as to the deceased or the sculptor. The sculptor is unknown [to me], but at least I can verify the name of the deceased and its location in St Marxer Friedhof.)

[THEMES: Guiding Angel; iconic Grieving Angel]

Grabmal von Margarete von Szily (1892-1929) und Familie, Döblinger Friedhof Wien

[THEMES: Guiding Angel; iconic Grieving Angel]

And finally, the monument for Beatrice Dofsky (1866-1923) in Friedhof Heitzing Wien. This bas-relief an almost exact replica of the Thorvaldsen Potocki 1829 monument. The only differences I can see - and they are extremely subtle - are in the hair and face, the abs, the wreath, and the draping of the modesty fabric. The inscription SINE LASSITUDINE means "Without Fatigue". I presume this refers to carrying on in life with all one's energy, despite one person's passing; or perhaps it was Frau Dovsky's personal motto and lifestyle.

[THEMES: Guiding Angel; iconic Grieving Angel]

Zentralfriedhof Wien - 11-12 October 2016

Zentralfriedhof Wien - The Vienna Central Cemetery - was opened in 1874, with an area of nearly 500 acres. Unlike the Italian Monumental Cemeteries, which typically were established because Napoleon decreed in 1804 that burials no longer could take place within city walls nor in churchyards, the Zentralfriedhof became necessary because the old district and church cemeteries no longer could accomodate the growing population.

Today, the cemetery covers nearly 600 acres - 2.4 square kilometres - and has more than 330,000 graves, with around 3 million total interments. (Source: Wikipedia.) The central building of the cemetery is the Friedhofskirche zum Heiligen Karl Borromäus, also known as the Dr-Karl-Lueger-Gedächtniskirche. The main building is flanked by two collonades (the East wing is seen in this picture) containing graves and their sculptural monuments.

The Karl-Borromäus-Kirche (Church of St Charles Borromeo) was built by architect Max Hegele between 1908 and 1911, though to my eyes it has a decidedly Art Deco look and feel to it (along with other influences, of course). I can't explain this, so I won't try. (I see Art Deco in many things.)

The grave of Johann Nepomuk Prix (1836-1894) is elaborate by any standards. He was, among other municipal posts, Bürgermeister (Mayor) of Vienna.

Hugo Wolf (1860-1903) was a renowned composer, known mostly for his art songs, or Lieder. His monument was created by Edmund von Hellmer (1850-1935) in 1904, and placed in an area of the Zentralfriedhof where many composers were buried, including Beethoven, Brahms, Schoenberg and Schubert. The sculptural style is apparently Symbolic, as distinguished from Classical or Realist, but to the casual observer (i.e., me) the symbolism is mysterious. Lovers kissing on the left, and a lone(ly) man obviously in agony on the right. Perhaps Wolf wrote songs about such things. In fact, that's pretty likely, come to think of it.

The grave of Clemens Pirquet (1874-1929) is another fine example of a bronze bas-relief set into a stone monument. May I say, it's about time for a bit of restoration.

[THEME: restoration]

Here in this portion of the monument for Emil von Kubinsky (1843-1907) and his family, sculptor Johannes Benk (1844-1914) has opted for Realism. This could be Kubinsky's actual family, grieving at his passing.

Rudolf Weyr (1847-1914) has sculpted a memorial for Dr Josef Weinlechner (1829-1906) that, once again, tests my ability to interpret Symbolic sculpture. I mean, am I the only one who sees the erotic overtones of this piece? (If so, I apologise both to Herr Weyr and Dr Weinlechner, as well as to you, the reader.)

What did I tell you when we were back in Bologna? This is hysterical. I can only imagine, if someone from this family showed up at Ellis Island (New York) during the immigration boom of the XIXth century, how the intake officer would go about explaining what they absolutely had to do to avoid the inevitable attention their name would bring. (But seriously, as with the family tomb marker in Italy noted above, I am not disrespecting this family or its departed, and I'm sure the humour of this situation is only due to the differences in Viennese and American/British cultures. This name, and probably the family, too, are completely respectable in Austria. It's only in English-speaking societies where the unintended double-entendres make the words funny. RIP.)

Now we get about as weird as we can find. First, what do we see? An infant, absolutely anatomically correct, in marble, being held by a chromium rabbit, in a pose that has led some in Vienna to nickname it "Pietà". But Michelangelo, it ain't. In fact, it's not even a grave nor a funerary monument to anybody. It's a piece of guerrilla art (my term) placed here surreptitiously, without anyone's consent, in 2010. The inscription on the base says simply, "Unbekannter Künstler 2010" ["The Unknown Artist 2010"]. A Web search reveals that it is actually the work of Adalbert Wazek (born 1968) and his "Street Art Project", with works placed all over Vienna in recent years. So, why hasn't it been removed, since it's not really a grave nor monument? It sits on "private" land between two adjoining graves, so the cemetery management has no authority to disturb it. Now that's artistic licence!

[THEME: weirdness]

The "Angel Writing" motif reappears here. Well, all right, the young artist (notice the palette and brushes at the base) drawing, here providing the flourishes under the name of artist Julius Berger (1850-1902) on this monument by Edmund Hoffman von Aspernburg (1847-1930).

[THEME: angel/person writing on monument]

This one is a bona-fide angel, sculpted by Johannes Benk (1844-1914), inscribing the name of [Friedrich Ritter von] Amerling (1803-1887) on his monument.

[THEME: angel/person writing on monument]

Finding this sculpture both solved a mystery and created another one. The Web has several posts of pictures of this haunting sculpture, most of them simply telling us that it's in "a Viennese cemetery".

The solved mystery: it's on the grave of Dr Otto Friedländer (1889-1963) in Gruppe 4, Reihe 3, Nr. 26.

The new mystery: the sculpture is signed, "Edm. Klotz" (see enlarged

portion above, with arrow pointing to the signature's location),

a Viennese sculptor who lived from 1855-1929.

Since the sculptor died more than 30 years before Dr Friedländer, the

only explanation I can think of is that this little angel is a ready-made

grave marker, or perhaps a re-purposed marker, obtained by the family after

the passing of the decedent.

[THEME: missing credit for deceased and/or artist on Web posts]

As fate would have it, just a few hours later when I was visiting the Friedhof at Hietzing (another district of Greater Vienna), I saw this cheap-looking, probably plastic knock-off of the sublime Klotz sculpture noted just above. It was not securely fastened to the grave, and may have been added after the fact. This lends some credibility to the idea that the Klotz sculpture may have been replicated for use on multiple graves, though I never saw another one in relatively thorough searches of four major Vienna cemeteries. As for this grave, I thought I had photographed the information I'd need to identify it, but the family name was hidden by the flowers. All I know is that the demised was "Evi, unser vielgeliebtes Mutterl" [Evi, our much-loved mother].

Döblinger Friedhof, Wien - 13 October 2016

I would classify this monument as Modernist, a memorial to several people with the plaque for Helga Ibl (1932-2008) at the top. What made this monument particularly interesting to me was the quotation inscribed in the plaque at the bottom: "Zärtlichkeit ist eine Existenzform. --J.P. Satre" Yes, Helga, Sartre's name on the plaque is missing one of the requisite "r"s. Oops. In fact, Oops permanently!

(The quote, according to www.marschler.at/ is from an interview with Jean-Paul Sartre in Die Zeit, 25 February 1977.)

This symbolic bas-relief memorializes Dr Ludwig Maier (1882-1933) and his family. Notice the skeleton hand upon the book being held by a "regular" hand. Another Symbolic mystery that I'll have to leave to the art historians.

I'm going to categorise this sculpture of a - shall we say - healthy angel as post-modern Wishful Thinking (a new category of art work), and leave all further interpretation to you, Gentle Reader.

[THEME: weirdness]

Grabmal Dr Avrel Ritter von Pichler (1867-1896), with a cherub writing "Auf wiedersehen!" on the family marker.

Here, a regular person (or perhaps an angel without wings) writes "Unvergesslich!" [Unforgettable] on the Rossi family gravestone.

Hietzinger Friedhof, Wien - 13 October 2016

This sad little boy appears on Pinterest and elsewhere, above the caption, "A Cemetery in Vienna". When I finally found a Web site that added "Hietzing" to the information, I was able to find him, weeping over the departed Dasatiel Family. To the boy's left, on the corner of the monument is the inscription "Ed[uard]. Hauser". Apparently Hauser (1840-1915) is the designer of the grave marker, while www.viennatouristguide.at/ credits Ludwig Dürnbauer (1860-1895) as the creator of the child sculpture. It looks like the sculpture might have been added after the monument was constructed, and may be a ready-made work of art.

After leaving Hietzing, walking back to the tram stop to return to central Vienna, my path went by the Pfarr- und Wallfahrtskirche Maria [Parish and Pilgrimage Church of Mary], first built on this site in 1419.

The relatively straightforward exterior gives way to this elaborate interior, not uncommon in the older churches of Vienna and elsewhere in Europe.

Behind the Maria-Kirche is the Schlosspark Schönbrunn. Let's just say they probably have more than one full-time gardener.

As a cultural center for centuries, Vienna certainly has its share of museums. In the Kunsthistorisches Museum, the room of Roman busts is both interesting and eerie.

On the streets of Vienna, like any city or town, shops try to be clever with their slogans and advertising, even to the point of posting an English phrase in a German-speaking country. So, Achill und Söhne [Achilles & Sons] love feet. I'll bet. Especially the heels, and/or tendons. (Think about it; you'll get it.)

Finally, some graffiti. Or perhaps I need to say, "Greffiti". And "99-percent Queliti", at that.

In Transit - Wien to Berlin

with a brief stopover in Praga (Prague) - 15 October 2016

A finger-drawing in the gunk on the window next to my seat on the Wien-to-Praga train. Entertaining. Sort of temporary graffiti.

In the Praga (Prague) railway station, this poster asks, "How do you like our entertainment portal on the train?", while the kid's thought-balloon says, "Who plays naughty!"

(NOTE: I depend heavily on Web-based language translators for these interpretations.)

Berlin City (East and West) - 16-17 October 2016

The marker for the grave of Wolf Kaiser (1916-1992) in Dorotheensätdischer Friedhof Berlin caught my attention. Here we have a Modernistic depiction of a hangman, and two other people. What could this mean? Was Kaiser hanged? Was he, himself, an executioner? Only after searching online for information did I learn that Kaiser was a well-known actor (I suppose most Viennese would have known this), most famous for his long-running performance in a revival production of Der Dreigroschenoper [The Threepenny Opera] by Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht. The headstone depicts two scenes from that production. (By the way: Bertolt Brecht is buried in the same cemetery.)

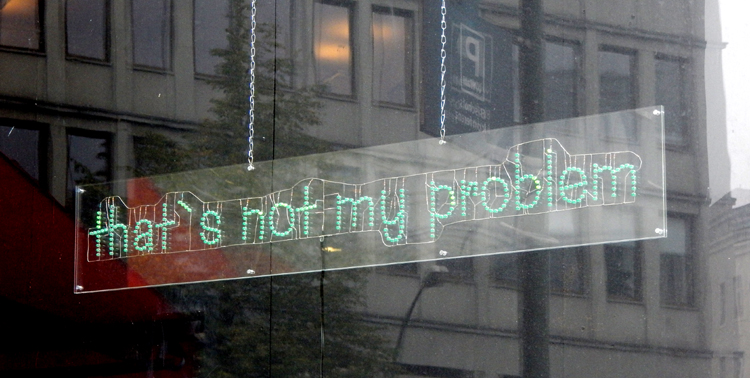

Berlin Greenpeace has chosen a startling way to get people's attention - and perhaps guilt them into, well, giving a fuck, and contributing to the cause. This sign was lighted, though the office was closed (at mid-day).

This sign, in a window just to the left of the one shown above, was not lighted.

Gimmicks to attract customers are as old as advertising, but Berlin's Oldest Beer Tap? People in Iowa are booking their vacations here, even as we speak.

A totally different experience from the Quell-Eck shown above is this stunning interior of the bar at the Mirchi Singaporean restaurant in the Oranienburger Straße. The whole décor apparently is translucent marble, for a stunning effect - even before you start drinking!

Berlin's Chausseestraße is an interesting neighborhood in many ways. Here, the whole side of a five-storey building is covered with graffiti. What amazes me is how tall the artists must be to write and draw above the first floor!

Berliners seem to be completely open and honest about what happened there during the nightmare of the Reich. This building originally was the Friedrichstraßenpassage Department Store (1904), and in the 1940s housed the Central Ground Office of the SS.

The inset at the right provides a closer look at the three-dimensional poster on the side of the building. The inscription reads, "Vor der Mauer, nach der Mauer, schickt der Staat die Wanzen" [Before the wall, after the wall, the State sends the bugs].

Speaking of Der Mauer, segments of the Berlin Wall have been left standing as a reminder of the horror and a caution against allowing anything like it again. Here, the wall has been partially stripped to show how it was constructed.

At this point, near the East Side Gallery and Wall Museum in the Mühlenstraße, the wall ends at a Curry Wurst stand.

This blurry photograph, taken from a moving tourist bus, shows the essence of the Zeitgeist in Berlin today, at least as it appeared to me. This sign appeared here for some time, over the doorway of the Michelberger Hotel in Warschauer Straße.

You may need to SCROLL TO THE RIGHT (or enlarge your browser window) to see this picture in its entirety.

This is the massive (to say the least) Hauptbahnhof, the Central Railway Station in Berlin, opened in 2006. This is the North side. Notice the silvery thingie at the left. We'll go in for a closer look at that.

The opening of the Hauptbahnhof in 2006 was also the debut of this remarkable sculpture, complete with moving parts, by Jürgen Goertz (born 1939). In all sources, it's called Rolling Horse. I don't think it has a German name. Even on German-language Web sites, it's referred to as Das Rolling Horse.

The Rolling Horse sculpture is quite complex. Since the Hauptbahnhof was built on the site of former railway stations, the base of the sculpture encases some relics from those old transportation hubs.

Perhaps this angle gives a better idea of just how big this beast is.

In a visit to Berlin's Bode Museum, I came upon this Reliquary Bust of a Saint Bishop, artist unknown, from Brussels c.1515/1520. You may remember way back at the top of this post (or you may not!) that one of the John the Baptist statues in Milano Cemetery was gesturing with two fingers in a manner similar to this bishop. I also had noticed it in a painting in a Genova museum, and elsewhere. It turns out that gesturing with two fingers, sometimes with the thumb turned in, sometimes extended, was an occult (hidden) blessing among early Christians. Of course, I can't help but comment that today, in England, two fingers held toward someone in just this way is a very rude gesture, indeed. Once again, the difference in cultures gives us cause to smile!

Here is Guardian Angel Protecting a Boy, a Lindenholz (linden wood) sculpture, artist unknown, from Suddeutschland (Bodensee) dated around 1670/1680. Note the two-finger gesture, similar to the Bishop above.

I spent some time trying to figure out this Eichenholz (oak wood) sculpture from Kalkar, dated around 1500. It's a representation of Abendmahl [Last Supper], and we can easily find Jesus in the center, but even if you count the head apparently under Jesus's right arm (who would certainly be the Apostle John), no matter how I try, I can't come up with twelve Apostles.

This unintended joke is just silly. The original smile intended by Andrea Della Robbia (1435-1525) for his untitled fountain figure (c.1490) was the tiny boy pulling up his frock to, how shall I say, "let go". Now that his little nether part has been knocked off, probably by some Mediæval vandal, it appears he's lifting his clothes to see what's missing.

The Bode Museum labels this intricate Lindenholz (linden wood) sculpture as Singende und musizierende Engel [Singing and Playing Angels], produced in the Tilman Riemenschneider Workshop in Heilingenstadt in about 1505. OK, I get that they're singing and playing, but how do we know they're angels? To me, they just look like well-dressed street (or church) musicians.